Author: Leilah J Dare / Editor: Jason Kendall / Reviewer: Martin Dore, Mehdi Teeli / Codes: CC11, CP1, SLO1 / Published: 10/03/2023

Context

Acute Pericarditis is a well-recognised cause of chest pain. Patients with pericarditis are seen commonly in the Emergency Department (ED): it is reported that 5% of patients presenting to the ED with non-ischaemic chest pain have acute pericarditis [2]. It is therefore a condition that Emergency Physicians should be familiar with.

Definition

Acute pericarditis is an inflammatory pericardial syndrome with or without pericardial effusion. [9]

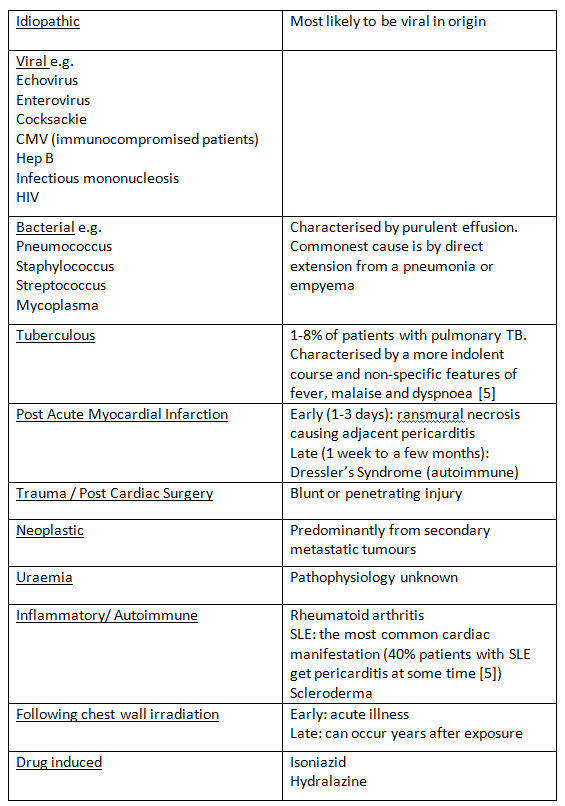

Aetiology

The causes of acute pericarditis are widespread and are listed in Table 1. Most cases are “idiopathic” (80-90%) [5]. Although labelled as idiopathic, the majority of these are likely to be viral in origin, but viral testing is not routinely done as it rarely alters the management and is not cost-effective.

The incidence of viral pericarditis is higher in young previously healthy adults and is lower in those patients who are subsequently found to need inpatient management. Patients with tuberculous pericarditis present with a less acute course. Patients with bacterial pericarditis present more acutely unwell and with other features of bacterial sepsis.

Learning Bite

Most cases of acute pericarditis in developed countries are based on viral infections which are self-limiting, with most patient recovering without complications.

Pathophysiology

The pericardium is composed of 2 layers: (i) the outer thicker fibrous pericardium and (ii) the inner visceral or serosal pericardium which is made up of a thin layer of mesothelial cells. In a normal physiological state the pericardial sac between these 2 layers contains 15-50mls of fluid. The combined thickness of these 2 layers should measure less than 2mm [1]. Pericarditis is caused by inflammation of the pericardial layers associated with varying amounts of pericardial fluid collection which may result in a significant pericardial effusion.

History

The clinical presentation is usually one of acute onset of chest pain; classically this is pleuritic in nature and eased by sitting up and leaning forward. The pain may be anywhere over the anterior chest wall, but it is usually retrosternal. It may radiate to the arm like ischaemic pain. A characteristic feature of the pain which is specific for pericarditis is radiation to the trapezius ridge [3]; the phrenic nerve traverses the pericardium and also innervates this muscle.

Learning Bite

Pain radiating to the trapezius ridge has high degree of specificity for pericarditis

Examination

Pericardial friction rub has been reported in around a third of cases [9]. This rub is often dynamic so repeated examination may be useful if it is not heard at the outset. It is heard maximally during expiration and is loudest at the lower left sternal edge. It can be distinguished from a pleural rub by the fact that it will still be heard when the patient holds their breath.

A diagnosis of acute pericarditis should be made when at least 2 out of 4 of the following criteria are met [9]:

- Characteristic chest pain

- Pericardial friction rub

- Suggestive ECG changes

- New or worsening pericardial effusion

Additional supportive findings include

Raised markers of inflammation (CRP/ESR/WCC) and evidence of inflammation by imaging technique (CT/CMR)

Other clinical findings associated with the aetiology of the pericarditis

(a) Fever:

A temperature over 38 degrees centigrade is a high risk feature for pericarditis. It may be associated with the presence of a bacterial infection (eg. a coexistent pneumonia).

(b) Clinical features of HIV:

HIV is associated with acute pericarditis in a number of ways. It can cause a direct infective pericarditis or pericarditis can be associated with other opportunistic infections such as CMV. Kaposi’s sarcoma and lymphoma can cause a non-infective pericarditis.

(c) Clinical features associated with autoimmune disorders:

Patients with the cutaneous or musculoskeletal features of rheumatoid arthritis, SLE and systemic sclerosis may be at risk of acute pericarditis relating to these diseases.

(d) Patients presenting after a STEMI:

This can occur early (within days) or late (months).

(e) Clinical features of Uraemia:

Patients with a raised urea may have non-specific features of nausea, vomiting, anorexia and itching. Pericarditis may occur in association with chronic or acute kidney injury.

(f) Metastatic Disease:

Metastatic lung and breast cancer are the commonest malignancies to cause acute pericarditis. The primary lung lesion may be seen on CXR

Other clinical findings associated with the complications of pericarditis

(a) Cardiac Tamponade:

The classic triad of distended neck veins, muffled heart sounds and hypotension (Beck’s triad) may not be present. Patients can have an insidious onset of tamponade and the symptoms and signs may be very non-specific. They may have orthopnoea, dysphagia, cough and occasionally episodes of loss of conciousness [9]. Echocardiography is required in all cases of suspected pericarditis in order to complete risk stratification (see below).

(b) Recurrent Pericarditis:

Patients may give a history of previous resolved episodes of chest pain, or of ongoing chest pain which has required a prolonged course of NSAIDs.

(c) Chronic Pericarditis:

This is defined as pericarditis lasting for more than 3 months. Symptoms include chest pain, palpitations and fatigue.

Risk Stratification

In order to appropriately risk stratify a patient with pericarditis, the emergency physician needs to consider the possible aetiology of the pericarditis along with the presence of high risk features. These high risk features (see Table below) are associated with a poorer prognosis and may help guide the need for inpatient management [5].

High risk features

- Fever (>38 C or 100.4 F)

- Subacute course

- Large pericardial effusion (echo-free space >20mm)

- Cardiac tamponade (of note the classic triad of distended neck veins, muffled heart sounds and hypotension (Becks triad) may not be present. Echocardiography is required in all cases of suspected pericarditis in order to complete risk stratification)

- Failure to respond to aspirin/non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) therapy.

- Myopericarditis (elevated troponin)

- Immunsuppression

- Trauma

- Oral anticoagulant therapy

Learning Bite

The presence of any high risk feature is associated with a poorer prognosis. These patients should be admitted for inpatient management.

To help establish the diagnosis and look for high risk features a number of simple investigations should be performed within the ED.

(i) Electrocardiography (ECG)

As well as looking for the characteristic features of pericarditis on the ECG it will also help to distinguish other potential causes of chest pain.

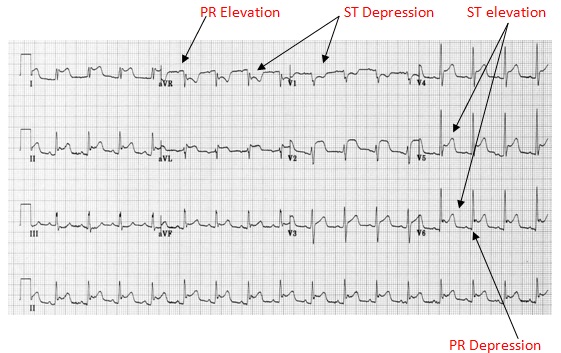

There are a number of ECG features which are characteristic of acute pericarditis (Fig 1):

Classically the evolution in pericarditis occurs in 4 stages:

- Stage 1 (acute phase within hours to few days) is characterised by diffuse ST elevation (typically concave up) and depression of the PR segment;

- Stage 2, typically seen in the first week, is characterised by normalisation of the ST and PR segments;

- Stage 3 is characterised by the development of diffuse T wave inversions, after the ST segments have become isoelectric;

- Stage 4 is represented by normalisation of the ECG or indefinite persistence of T wave inversions.[6]

Typical ECG changes however have been reported to occur in only 60% of cases. [12]

Fig 1 demonstrates the acute phase and demonstrates the ECG findings likely to be seen in the ED.

The above ECG changes are seen in the acute phase of pericarditis and are likely to be seen within the ED. As the disease progresses so may the ECG: there may be notched T waves, biphasic T waves or T wave inversion. These T wave changes may last for weeks or months but are of no clinical significance if the patient has recovered clinically.

Dysrhythmias are uncommon in pericarditis and if present may indicate myocardial involvement (Myopericarditis).

The ECG changes seen in pericarditis can be confused with Benign Early Repolarisation (BER). The most reliable ECG distinguishing feature is seen in lead V6. Specifically, when the ST elevation (mm) to T wave height (mm) ratio is greater than 0.25 acute pericarditis is more likely than BER (Figs 2 and 3) [7].

Learning Bite

ST:T wave ratio in V6 can be used to help discriminate between BER and Acute Pericarditis [7]

Fig 2: (i) Benign Early Repolarisation:

Fig 3: (ii) Pericarditis:

(ii) Troponin

Troponin levels may be measured and are raised in 30-70% of patients with acute pericarditis. This does not offer any prognostic information [8]. A troponin rise is partially related to the extent of coexisting myocardial inflammation but, unlike in acute coronary syndromes, elevation in troponin is not associated with adverse outcome in pericarditis [13]. However, if the troponin is raised the patient should be considered to have myopericarditis and as this is a feature of poor prognosis further inpatient workup should be considered.

(iii) Haematology

A full blood count should be performed looking for an increase in the white cell count (WCC). A mild lymphocytosis is common. Significantly raised WCC is an indicator of poor prognosis and will therefore make inpatient management more likely.

(iv) Echocardiography (ECHO)

The use of Echocardiography is important to help aid diagnosis and to consider the presence of large pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade which are poor prognostic factors potentially requiring further management. Studies have demonstrated that Up to 60% of patients may have a mild-moderate pericardial effusion, whilst around 5% were shown to have cardiac tamponade. [12]

(v) Chest X-ray (CXR)

CXR is generally performed to look for alternative causes of chest pain. There may be radiological features of pneumonia if bacterial pericarditis is suspected or mass lesions indicative of neoplastic disease.

(vi) Computerised tomography of the chest (CT)

CT of the chest may be performed to look for alternative diagnoses such as acute aortic dissection or pulmonary embolism.

Myopericarditis vs Pericarditis

Acute pericarditis may be accompanied by some myocardial involvement. Once the diagnosis of acute pericarditis has been made one should consider whether there is any myocardial involvement. Troponin cannot be used to discriminate alone [9], however new onset of focal or depressed LV function on echocardiography would indicate inflammatory involvement and damage to the myocardium. A diagnosis of myopericarditis requires full clinical assessment including ECG, troponin and Echocardiography.

Learning Bite

Although Troponin levels are elevated in 30-70% of patients with pericarditis, and alone they offer poor prognostic information[8], the presence will warrant further assessment to exclude myopericarditis.

Other investigations

C-reactive protein

Elevated C-reactive protein is consistent with an inflammatory state [15].

Serial measurements may be helpful for monitoring disease activity and response to therapy [9].

Serum urea and electrolytes

Elevated levels of urea (particularly >21.4 mmol/L [>60 mg/dL]) suggest a uraemic cause [15].

In absence of high risk features these patients can be managed in the community.

The mainstay of treatment is activity restriction and symptomatic treatment in the form of anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDS)

Patients should be instructed to restrict strenuous physical activity until symptoms have resolved and biomarkers have normalized. Athletes should be advised not to compete in competitive sports for at least 3 months following resolution.

Drug treatments

Any obvious underlying cause for acute pericarditis should be treated (eg. pneumonia, tuberculosis, uraemia, etc.).

NSAIDS are the mainstay of treatment for pericarditis (e.g. aspirin, ibuprofen, indomethacin, etc.). Aspirin is used preferentially if pericarditis is a complication of acute myocardial infarction.

Adding colchicine to NSAIDS should be strongly considered as it has been shown to reduce symptoms, decrease the rate of recurrent pericarditis, and the low dose regimen (0.5-1.2mg daily) is generally well tolerated. [14]

It has been recommended that NASIDS can be stopped after resolution of symptoms but colchicine should be continued for 3 months.

Patients who fail to respond to initial treatment within 1-2 weeks should be admitted to hospital for further assessment.

Steroids are not indicated for acute pericarditis in the early phase as they are associated with an increased risk of relapsing pericarditis. Steroids should only be considered as first line treatment when the underlying cause is thought to be immune-mediated, due to a connective tissue disorder, or in uraemic pericarditis [9].

Learning Bite

First line drug treatment for uncomplicated acute idiopathic pericarditis is NSAIDs and colchicine.

Complications

Studies evaluating the aetiology of acute pericarditis reported that a specific cause was found in 17% of patients and that most complications were seen in these patients [10]. Complications included acute cardiac tamponade (3.1%) and chronic constrictive pericarditis (1.5%).

Purulent pericarditis associated with tamponade is potentially fatal and requires urgent drainage and intravenous antibiotics; it carries a mortality rate of 40%.

Relapsing pericarditis occurs in 15-30% of patients with a presumed idiopathic aetiology, a small proportion of whom go on to suffer chronic relapsing pain.

Emerging Treatment

Rilonacept

Rilonacept is a subcutaneously injected interleukin-1 alpha and beta cytokine trap approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in adults to treat recurrent pericarditis and to reduce risk of recurrence in adults and children aged 12 years and older. Among patients with recurrent pericarditis and systemic inflammation in the RHAPSODY trial, rilonacept led to rapid resolution of recurrent pericarditis episodes and to a significantly lower risk of pericarditis recurrence compared with placebo [16] It is not currently approved in Europe for this indication.

Key Learning Points

- 5% of patients presenting to the ED with non-ischaemic chest pain have acute pericarditis. Level of Evidence B

- Pain radiating to the trapezius ridge is specific for acute pericarditis

- 80-90% of acute pericarditis is viral in origin and often labelled as “idiopathic”. Level of Evidence B

- The presence of any one of the high risk features is associated with a poorer prognosis. These patients should be admitted for inpatient management. Level of Evidence B

- ST:T wave ratio in V6 can be used to help discriminate between benign early repolarisation and acute pericarditis [7].Level of evidence B

- Troponin levels are elevated in 30-70% of patients. They offer no prognostic information[8].Level of evidence B

- NSAIDs are the mainstay of treatment for acute idiopathic pericarditis.Level of Evidence B

Pitfalls

- The main pitfall for the emergency physician is not carrying out a full risk stratification (including an echocardiogram) before declaring the patient suitable for discharge.

- Misselt AJ, Harris SR, et al. MR Imaging of the pericardium. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2008 May;16(2):185-99, vii.

- Fruergaard P, Launbjerg J, Hesse B, Jørgensen F, et al. The diagnoses of patients admitted with acute chest pain but without myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 1996 Jul;17(7):1028-34.

- Le Winter M, Tischler M. Pericardial Diseases. In Bonow: Braunwald’s Heart Disease –A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, 9th ed. Chapter 75.

- Khandaker MH, Espinosa RE, et al. Pericardial disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010 Jun;85(6):572-93.

- Lange RA, Hillis LD. Clinical practice. Acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2004 Nov 18;351(21):2195-202.

- Spodick DH. Acute pericarditis: current concepts and practice. JAMA. 2003 Mar 5;289(9):1150-3.

- Ginzton LE, Laks MM. The differential diagnosis of acute pericarditis from the normal variant: new electrocardiographic criteria. Circulation. 1982 May;65(5):1004-9.

- Body R, Ferguson C. Should we be measuring troponins in patients with acute pericarditis? Emerg Med J 2008;25:253-524.

- Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, Badano L, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

- Imazio M, Cecchi E, Demichelis B et al. Indicators of poor prognosis of acute pericarditis. Circulation 2007;115:2739.

- Eppert A, Baombe J. Colchicine as an adjunct to non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of acute pericarditis. Emerg Med J 2011:244-245.

- Imazio M, Demichelis B, Parrini I, et al. Day-hospital treatment of acute pericarditis: a management program for outpatient therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Mar 17;43(6):1042-6.

- Imazio M, Trinchero R. Triage and management of acute pericarditis. Int J Cardiol. 2007 Jun 12;118(3):286-94.

- Alabed S, Cabello JB, Irving GJ, Qintar M, Burls A. Colchicine for pericarditis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Aug 28;(8):CD010652.

- Ariyarajah V, Spodick DH. Acute pericarditis: diagnostic cues and common electrocardiographic manifestations. Cardiol Rev. 2007 Jan-Feb;15(1):24-30.

- Klein AL, Imazio M, Cremer P, et al. Phase 3 trial of interleukin-1 trap rilonacept in recurrent pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2021 Jan 7;384(1):31-41.

8 Comments

Useful article detailing the key learning points regarding pericarditis throughout.

Very helpful, especially in highlighting the role of echo prior to discharge

Very helpful material.Thank you.

very nice

very nice and clinically helpful revision of one of the causes of chest pain in ED patients.

very nice

Useful whistle stop tour on pericarditis and high risk features warranting admission.

good recap

ECHO in department is good for safety netting and follow up