Author: Evan Coughlan, Andrew Parfitt / Editor: Helen Blackhurst / Reviewer: Ahmad Alabood / Codes: OncC1, OncP1, SLO1, UC2, UC7, UP6 / Published: 27/03/2023

Context

Haematuria is the presence of red cells in urine. It is abnormal and always requires further investigation. It may be macroscopic (visible to the naked eye) or microscopic (when 3-5 red blood cells per high power field are seen). Both are commonly encountered in the emergency department [1].

Health screening programmes have found haematuria to be present in 2-4% of men and 8-11% of women [4]. Microscopic haematuria is most often an incidental finding, but may be associated with malignancy in up to 10% of cases [2]. Somewhat worryingly, studies have shown that 39% of patients with microscopic haematuria on screening analysis do not receive correct follow up testing [14]. Malignancy has been reported in up to 34% of cases of macroscopic haematuria [2].

Learning bite

Haematuria is considered urinary tract malignancy until proven otherwise. All patients with haematuria need rapid follow up and should be referred to 2 week wait urology clinics. Gross hematuria more often indicates a lower tract cause, whereas microscopic hematuria tends to occur with kidney disease.

Clinical Assessment

| Risk factors for developing urological cancer |

| Age >40 |

| Smoking |

| Exposure to occupational chemicals (benzenes, aniline dyes and aromatic amines) |

| Cyclophosphamide |

| Analgesic abuse |

| Prior pelvic irradiation |

| Recurrent UTI |

| Schistosomiasis infestation |

Haematuria may be painless and asymptomatic or painful. All patients with haematuria need rapid follow up and should be referred to 2 week wait urology clinics due to the risk of malignancy [6].

Medical history

In addition to a full past medical history, family history and genitourinary history, risk factors for urological cancer should be sought. These include age >40, smoking, exposure to occupational chemicals (benzenes, aniline dyes and aromatic amines), cyclophosphamide, prior pelvic irradiation, analgesic abuse, recurrent UTI and schistosomiasis infestation.

Learning bite

Risk factors are used to identify patients at increased risk of malignancy. Painless hematuria is more often due to neoplastic, hyperplastic, and vascular causes.

Timing

The timing in relation to the stream should be noted. Initial haematuria suggests a urethral source whereas terminal haematuria indicates a bladder neck or prostatic urethra source. Haematuria through the stream suggests bladder or upper tract pathology. Hematuria occurring between voiding and noticed only as staining of underclothes with blood, while voided urine is clear, indicates lesions at the distal urethra or the meatus. Prostatic bleeding is usually in the setting of a strong history of prostatic symptoms. Gross haematuria with clots represents significant bleeding and is a worrying sign of malignancy. Haematuria and colicky flank pain with stringy clots may suggest upper tract bleeding. Constant severe lower abdominal pain and haematuria may suggest clot retention. Large renal cell carcinomas can invade the renal pelvis and cause frank haematuria and clot colic.

Associated urinary symptoms

Full enquiry must be made of associated urinary symptoms. The most frequent scenario will be a female with history of frequency and dysuria who has microscopic haematuria in association with white cells and nitrites in the blood.

Systemic symptoms

Systemic symptoms and recent weight loss must be enquired for. A history of upper respiratory tract symptoms and possible streptococcal sore throat should be sought, to exclude post streptococcal glomerulonephritis and a consequent acute nephritic syndrome that can lead to long term renal problems [7,8]. Gastrointestinal symptoms may be a part of haemolytic uraemic syndrome and atrial fibrillation may result in renal emboli and haematuria. Sexual history, including recent coitus, must be noted as haematuria is common post coitally.

Learning bite

The acute nephritic syndrome is a feature of many systemic disorders and, in addition to haematuria, there is usually proteinuria with systemic symptoms. Hematuria that varies with menstruation and is associated with severe dysmenorrhea may indicate endometriosis involving the urinary tract.

Drug history

Drug history is important: penicillin, NSAIDS and cephalosporins can all cause interstitial nephritis [9]. Cyclophosphamide can cause haemorrhagic cystitis. Between 4 and 24% of patients on anticoagulants can develop haematuria [7]. They should be investigated in the same manner as those not on anticoagulants.

Physical examination

A full physical examination must be documented, paying particular attention to the presence of palpable bladder and masses per abdomen, rectally or pelvic. Close inspection of the vagina, including cervix, and male external genitalia should be performed. Vaginal bleeding must be excluded and this may require vaginal and speculum examination of the female patient. In such cases, careful inspection of the urethral area may reveal caruncles.

Specific rashes of conditions such as Henoch-Schonlein purpura and lupus should be sought.

Clinical Assessment – Haematuria

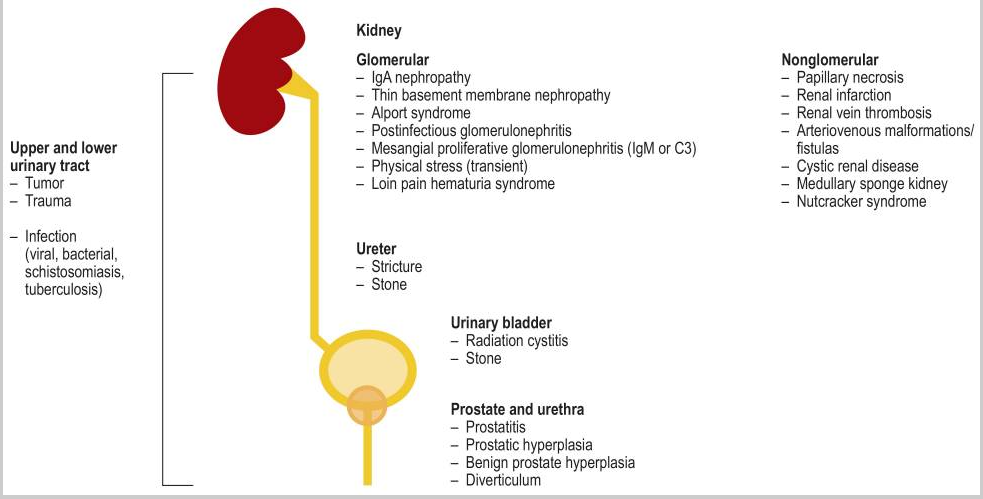

Haematuria can arise from a number of situations.

Exercise haematuria

This can occur after non contact strenuous exercise such as swimming and running. It is caused by blunt trauma of the posterior bladder wall against the trigone. It should settle over 48-72 h and, as long as it does, requires no further investigation.

Factitious haematuria

This is extremely rare and, although all emergency physicians will see the occasional addict seeking opiates, it should only be considered as a diagnosis following comprehensive exclusion of other causes.

Post ejaculatory haematuria

This may be associated with a urethral haemangioma or occur following prostate trauma, such as bicycling on hard saddles.

Learning bite

Free hemoglobin, myoglobin, or porphyrins in the urine result in a positive urine test strip reaction for blood.

It is important to note that there is no correlation between the extent of haematuria in a patient and the extent and severity of underlying disease. In addition, up to 4% of patients with normal dipsticks have abnormal microscopy [3]. In the standard urine dipstick test, leucocyte esterase detects the presence of white blood cells present in the urine as a consequence of inflammation or infection. Remember, a negative dipstick result does not exclude a UTI. False positive readings are far less common than false negative results.

Other causes of sterile pyuria:

- Stones

- Tubulointerstial nephritis

- Papillary necrosis

- TB

- Interstitial nephritis

White cells can persist in urine for some time after treatment so, again, it is important that symptoms are sought and treatment not started blindly.

Learning bite

A negative urine dipstick does not rule out urinary tract infection.

Nitrates

Nitrates are converted to nitrites in the bladder following a period of incubation with organisms. This is most reliable when used on the first void of the day. Nitrite detection has a positive predictive value of 96% for urinary tract infection, but a low negative predictive value. Acid pH will rule out renal tubular acidosis as a cause of nephrolithiasis, and alkaline pH typically results from infection with organisms that split urea with urease e.g. proteus and pseudomonas.

Urine culture

Routine urine culture is not needed in a young female with typical symptoms and positive nitrites and leucocytes. In all other cases – especially males, the immunocompromised, pregnant women and those with UGT obstruction and treatment failures – it is essential. Males have a longer urethra; UTIs are therefore less common and may indicate underlying pathology. Recurrent persistent infection needs investigation to exclude sinister causes.

Learning bite

Delays in transporting samples to the lab, especially leaving them in the warm environment of the emergency department, produces false positive results. Therefore, samples should be transported and refrigerated promptly.

Dipstick blood test

The dipstick test for blood looks at haemoglobin-like components and does not differentiate between haemoglobin from red cells and myoglobin from the breakdown of skeletal muscle. Note, also, that there is no correlation between the quantity of red blood cells seen and the degree of obstruction. Likewise, total obstruction may initially have no red cells present.

Study

Sugimura et al studied 823 patients presenting with microhaematuria over 5 years, between 1993 and 1998. They established the respective positive predictive values for a positive dipstick in bladder cancer of 1.7% and renal cancer of 0.2%. In patients over 50 years old the risk of bladder cancer in those with microscopic haematuria rose to 6.2% [12]. Long term follow up studies show those with a negative microscopy have no increase in risk of urological disease [3].

A negative repeat dipstick should not cease further investigation, as it has been found that patients with an initial positive test may still have an underlying abnormality, even if subsequent repeated tests are normal.

Careful urine microscopy is essential; red cell casts in the urine may indicate bleeding from the kidney most often due to the glomerulonephritides. Red cell casts are always abnormal. White cell casts may be seen in pyelonephritis. Hyaline casts are precipitated protein; these can be seen after exercise, but granular casts are a sign of pathological proteinuria of tubular and glomerular disease.

Significant proteinuria is rare without UTI. It is indicative of a kidney cause, such as tubulointerstitial, renovascular or systemic disease. Urine sticks can detect as little as 100 mg/L proteinuria. The predominant protein detected is albumin.

Urine dipsticks are insensitive at detecting globulins and Bence Jones protein in myeloma. 24 h collection is indicated if urine is positive for protein. Selective determination of protein type can be performed using electrophoresis e.g. albumin, immunoglobulins.

Microalbuminuria is an early indication of diabetic renal disease. Proteinuria may be associated with postural changes, exercise and can occur in patients with a pyrexia.

Urine cytology is reliable only for high grade transitional tumours and is less sensitive for detecting low grade transitional cell tumours.

The initial aim in the investigation of haematuria must be to rule out urological malignancy. Management should proceed along the lines of the flow chart below. Following the algorithm will end in cystoscopy if coexistent disease such as stone disease is not detected.

Causes of Discoloured Urine

Patients frequently complain of discoloured urine. The table below lists common causes of urine discolouration that are often seen in practice.

Table 2: Causes of discoloured urine

| Colour | Cause |

| Dark Yellow |

|

| Orange |

|

| Blue Green |

|

| Red Brown |

|

| Red |

|

Renal Causes of Haematuria

There are many renal causes of haematuria encountered in clinical practice. Think of general disease processes and of anatomical locations to help recall these causes. Remember, however, that infection and renal colic are the most commonly encountered. Malignancy is rare, but it must be ruled out.

Table 3: Renal Causes of haematuria

| Infection |

UTI Pyelonephritis TB |

| Neoplasia |

Renal cell carcinoma Oncocytoma Transitional cell carcinoma Metastatic tumours UGT Angiomyolipoma |

| Iatrogenic | Instrumentation Biopsy |

| Metabolic | Calculi |

| Trauma | Blunt and penetrating |

| Inflammatory |

Interstitial nephritis Post streptococcal IgA nephropathy Goodpasture’s syndrome |

| Radiation | Nephritis |

| Vascular |

Renal venous thrombosis Renovascular arterial disease Haemangioma Renal papillary necrosis |

| Congenital |

Pelvi-ureteric junction obstruction Cystic renal disease Arteriovenous malformation |

| Genetic |

Renal tubular acidosis Type1 Cystinuria Von Hippel-Lindau disease Alport syndrome Thin basement member disease |

Non-Renal Causes of Haematuria

Causes of haematuria originating in the bladder, ureter, prostate and urethra are listed in the table below.

Table 4: Non-renal causes of haematuria

| Ureteral | Metabolic Neoplastic Trauma Foreign Bodies |

Calculi Transitional cell carcinoma Including iatrogenic Stent |

| Bladder | Neoplasia |

Transitional cell carcinoma Squamous cell carcinoma Adenocarcinoma Neuroendocrine tumours |

| Anatomical |

Diverticula Vesicoureteric reflux |

|

| Infection | Cystitis Schistosomiasis | |

| Inflammatory |

Interstitial cystitis Cyclophosphamide cystitis |

|

| Metabolic |

Calculi Post acute urinary retention |

|

| Prostate |

Benign prostate hypertrophy Adenocarcinoma Prostatitis Calculi |

|

| Urethra |

Haemangioma tumour Stricture trauma Foreign body instrumentation |

Haematuria in Specific Clinical Situations

There are several specific situations within haematuria management:

Positive urine culture

Haematuria with a positive urine culture in females requires treatment with culture specific antibiotics. Haematuria in similar circumstances in the male always requires referral. Microscopic haematuria in females with recurrent UTIs also requires investigation as per protocol.

Microscopic haematuria

It must be noted that a single episode of microscopic haematuria with any risk factor for malignancy will mandate cystoscopy, imaging and cytology. Determination that there is a low risk of malignancy does not mandate all of these. In this case, imaging is usually performed of the upper tract, followed by flexible cystoscopy if abnormalities are found.

Ideally, all patients who are high risk should have an intravenous urogram and an ultrasound, as there is a risk of missing a cancer if only one is used.

Learning bite

A male with features of UTI and haematuria on dipstick should be followed up urologically and not merely given culture sensitive antibiotics.

Gross haematuria

Gross haematuria can lead to clot retention and severe abdominal discomfort. The patient may require resuscitation and haematological investigations including FBC, clotting and cross match. This condition requires irrigation with a three way large haematuria catheter, until the urine is clear, and subsequent cystoscopy. Failure to clear the urine through bladder washout will require a continuous infusion through one of the ports on the catheter.

Macroscopic haematuria

Macroscopic haematuria has a high diagnostic yield for urological malignancy. In men over 60 the positive predictive value for macroscopic haematuria for malignancy is 22.1% [10].

Learning bite

Intravenous urogram (IVU), ultrasound, cystoscopy and cytology are required to rule out sinister causes of haematuria.

Intractable haematuria

Intractable haematuria can occur in radiation cystitis, bladder carcinoma and cyclophosphamide.

Renal biopsy

The role of renal biopsy in patients with isolated haematuria is not yet clearly understood. There are structural glomerular abnormalities in many of these patients, but they appear to be at low risk for progressive disease [8].

Patients with microscopic haematuria, proteinuria (500 mg or more on 24 h collection), casts, dysmorphic red blood cells or elevated serum creatinine should be referred to nephrologists for a renal biopsy. It is unusual for haematuria of a surgical/urological cause to produce protein concentration >200 mg/dl. The management of nephrological diseases will depend on the specific findings of biopsy.

Follow up

The reliability of an investigation protocol such as that in the algorithm shown on the right has been demonstrated in a number of studies. Howard and Golin followed a cohort of such patients over 20 years and there was no incidence of renal abnormality [7]. Khadra et al followed a large cohort for 2.5-3 years and there were no abnormal findings [3].

Imaging in haematuria investigation may involve the following:

Intravenous urography

The plain kidney ureter bladder (KUB) film will reveal 70-80% of renal stones. Intravenous urogram (IVU) has a lower cost and radiation dose than CT although CT protocols are evolving. IVU involves administration of contrast, which can cause anaphylactic reactions and must not be used in renal failure.

Metformin must be stopped for 48h prior to the study to avoid renal failure and lactic acidosis. Additional contraindications include asthma, pregnancy and sea food allergy. In many centres, IVU remains the main investigation for renal colic, but juniors often have difficulty interpreting the images. It certainly does not reliably diagnose an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). It is more effective at diagnosing transitional cell carcinomas than US, but has a limited sensitivity in detecting small renal masses that are less than 2 cm in diameter.

CT

Non contrast CT is especially useful in stone disease. The study may well reveal the offending stone and quantify the degree of hydronephrosis. Ninety nine percent of stones are seen on non contrast helical CT, including urate and xanthine stones that are radiolucent on a kidney ureter bladder (KUB) film. Modern CT protocols can also approach the radiation dose of IVU. Contrast CT can determine whether cystic renal lesions are malignant or not [8,9]. Signs may also be evident of recent stone passage.

Most importantly, in an emergency department setting, the CT can identify or rule out other causes for the clinical picture, such as AAA. Renal carcinoma is increasing in incidence and, although still rare, may be found whilst investigating for renal stone disease.

Endoscopy

Endoscopy allows the urologist to rule out small mucosal lesions within the urinary tract. Flexible cystoscopy is often performed in a ward/day case environment prior to formal theatre and, if the urine is clear, the diagnostic accuracy is equivalent.

Diagnostic uncertainty or difficulty would involve resorting to rigid cystoscopy. Likewise, difficulty accessing the bladder with a flexible scope due to large prostate or stricture, for example, would be an indication for formal rigid cystoscopy.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is excellent at visualising renal cystic masses and hydronephrosis. It can assess renal morphology, structure and vasculature and assess bladder wall and emptying. It is less sensitive than IVU in the diagnosis of uroepithelial tumours.

CT is more sensitive than ultrasound in detecting renal masses and tumours. Khadra estimated 43% of renal tumours would have been missed, if ultrasound alone had been used, in 1930 patients over 2.5 years [3]. Ultrasound sensitivity for detecting calculi is low at 37-64%. However, ultrasound is easily available and the safe investigation of choice in pregnancy.

- Keeler B, Ghani RK, Nargund V. Haematuria 1: risk factors, clinical evaluation and laboratory investigations. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 2007; 68(8): 419.

- Sultana SR, Goodman CM, Byrne DJ, Baxby K. Microscopic haematuria: urological investigation using a standard protocol. Br J Urol. 1996 Nov;78(5):691-6; discussion 697-8.

- Khadra MH, Pickard RS, Charlton M, Powell PH, Neal DE. A prospective analysis of 1,930 patients with hematuria to evaluate current diagnostic practice. J Urol. 2000 Feb;163(2):524-7.

- Thompson IM. The evaluation of microscopic hematuria: a population-based study. J Urol. 1987 Nov;138(5):1189-90.

- Harper M, Arya M, Hamid R, Patel HR. Haematuria: a streamlined approach to management. Hosp Med. 2001 Nov;62(11):696-8.

- Coxon JP, Harris HJ, Watkin NA. A prospective audit of the implementation of the 2-week rule for assessment of suspected urological cancers. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003 Sep;85(5):347-50.

- Golin AL, Howard RS. Asymptomatic microscopic hematuria. J Urol. 1980 Sep;124(3):389-91.

- Ghani RK, Keeler B, Nargrund A. Haematuria 2: imaging investigations, management and follow up. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 2007 68:9, 489-493.

- McDonald MM, Swagerty D, Wetzel L. Assessment of microscopic hematuria in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2006 May 15;73(10):1748-54.

- Hicks D, Li CY. Management of macroscopic haematuria in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2007 Jun;24(6):385-90.

- Murakami S, Igarashi T, Hara S, Shimazaki J. Strategies for asymptomatic microscopic hematuria: a prospective study of 1,034 patients. J Urol. 1990 Jul;144(1):99-101.

- Sugimura K, Ikemoto SI, Kawashima H, Nishisaka N, Kishimoto T. Microscopic hematuria as a screening marker for urinary tract malignancies. Int J Urol. 2001 Jan;8(1):1-5.

- McCartney MM, Gilbert FJ, Murchison LE, et al. Metformin and contrast media–a dangerous combination? Clin Radiol. 1999 Jan;54(1):29-33.

- Sutton JM. Evaluation of hematuria in adults. JAMA. 1990 May 9;263(18):2475-80.

2 Comments

Well presented and very useful

good refreshment