Authors: Derek Obiri, Charlotte Davies / Editor: Swagat Mishra / Codes: HC9, SLO3 / Published: 26/12/2023

We transfuse lots of blood in the emergency department (ED), and before we can even consider the science behind massive transfusions, we should consider the basics of transfusion. Transfusion may seem simple, but here are few reminders and updates on the basics of transfusion starting with the transfusion ten commandments – for many of us medical school was our last training!

You can read the first part of the blog here.

2. Results of laboratory tests are not the sole reason for deciding on transfusion.

3. Transfusion decisions should be based on clinical assessment underpinned by evidence-based clinical guidelines.

4. Not all anaemic patients need transfusion (there is no universal ‘transfusion trigger’).

Anecdotally we know that some providers prescribe more blood transfusions than others. Reducing the number of blood products transfused in the emergency department would reduce financial cost, workload, and the possibility of having transfusion reactions. Knowing when blood is clinically indicated relies on you being up to date with the evidence base. Although the clinical indication for blood products is checked by the blood transfusion scientist, they would never decline blood products. Each trust will have quantitative transfusion targets.

Clinical Indication for Transfusion of Blood Products

|

Red Cell Indication |

Hb < 70g/L |

Hb < 80g/ + risk factors (cardiovascular disease, elderly, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, diabetes) |

|

| Clinical decision (acutely unwell, haematology advice) | |||

| Platelet | Platelets <10 x x 109/L |

Platelets <20 x 109/L + risk factors (e.g. sepsis) |

Platelets <75 x 109/L on critical care |

|

Platelets <50 x 109/L pre-op |

Platelets <100 x 105/L pre brain or eye surgery |

Platelets <100 x 105/L + major trauma |

|

| Clinical decision (acutely unwell, haematology advice) | |||

The difficult bit about this is deciding whether a patient is acutely unwell or not. We know anaemia can cause fatigue and shortness of breath. At which point does that require a blood transfusion, and at which point is (assuming it is due to iron deficiency) an iron transfusion enough?

5. Discuss the risks, benefits and alternatives to transfusion with the patient and gain their consent.

Consent is probably part of your trust’s blood transfusion policy, and to be able to gain valid consent you need to ensure consent has been obtained. There are leaflets to help you indicate to your patient what the risks of transfusion are – but how often do you honestly ask your patients for consent? Empower your patient to support positive identification.

The RCOA has empowered patients with some nationally produced information leaflets about the risk of anaesthesia and maybe we need a push to similarly empower patients before blood transfusion. Tell your patients about the risks of blood transfusion. Going a step further, does your trust have a standard consent form for patients about to receive a blood transfusion? Do you get written consent? Do you even get informed consent? Potential example below:

6. The reason for transfusion should be documented in the patient’s clinical record.

The transfusion ‘prescription’ must contain the minimum patient identifiers and specify:

- Components to be transfused

- Date of transfusion

- Volume/number of units to be transfused and the rate or duration of transfusion

- Special requirements (e.g. irradiated, CMV negative, HbS negative). Check your trust’s policy but broadly includes those with aplastic anaemia, stem cell transplants, Hodgkin’s disease, congenital immunodeficiency and neonates.

7. Timely provision of blood component support in major haemorrhage can improve outcome – good communication and team work are essential.

We will update our major haemorrhage blog soon! Every blood transfusion should be seen as a practice for the emergency major haemorrhage transfusion. Make sure that you’re ready to transfuse blood as soon as it arrives.

- Good IV access

- Wristband on patient.

- Blood administration set (170–200 μm integral mesh filter) ready.

Blood transfusions must be completed within 4 hours of removal from controlled temperature storage. Many patients can be safely transfused over 90–120 minutes per unit. A dose of 4 mL/kg raises Hb concentration by approximately 10 g/L (70 kg man)

Platelets must be started as soon as possible after they arrive, usually over 30-60 minutes. One adult therapeutic dose (ATD) (pool of four units derived from whole blood donations or single-donor apheresis unit) typically raises the platelet count by 20–40×109/L.

FFP should not be used to reverse warfarin (prothrombin complex is a specific and effective antidote. The dose is typically 12–15 mL/kg, determined by clinical indication, pre-transfusion and post-transfusion coagulation tests and clinical response, with an infusion rate of 10–20 mL/kg/hour (except in major haemorrhage). Careful haemodynamic monitoring to prevent TACO is essential.

Cryoprecipitate will raise fibrinogen concentration by approximately 1 g/L in average adult. The typical adult dose is two five-donor pools (ten single-donor units). It is typically administered at 10–20 mL/kg/hour (30–60 min per five-unit pool).

8. Failure to check patient identity can be fatal. Patients must wear an ID band (or equivalent) with name, date of birth and unique ID number. Confirm identity at every stage of the transfusion process. Patient identifiers on the ID band and blood pack must be identical. Any discrepancy, DO NOT TRANSFUSE.

We all know this but aren’t very good at doing this. Let’s break it down into component parts.

a) Positive identification of the patient. The importance of doing this properly is highlighted in this fabulous video from patient blood management England, covering the strange case of Penny Allison. Remember to ask patients what their name is, not “are you Penny Allison”.

Minimum patient identifiers are:

- Last name, first name, date of birth, unique identification number.

- Whenever possible ask patients to state their full name and date of birth.

- For patients who are unable to identify themselves (paediatric, unconscious, confused or language barrier) seek verification of identity from a parent or carer at the bedside. This must exactly match the information on the identity band (or equivalent).

- All paperwork relating to the patient must include, and be identical in every detail, to the minimum patient identifiers on the identity band.

b) Labelling of the sample – labelling for blood transfusion samples must be handwritten at the patient’s bedside to reduce the chance of mislabelling. This is a safety mechanism designed to make things safer – not designed to irritate you. Think carefully about your trust. How often does the laboratory “reject” a sample as it’s not been labelled properly, or incident form incorrectly labelled bloods? These “wrong blood in tube” (WBIT) incidents are the warning signs that something is going wrong with blood labelling – and it might be irksome to re-bleed a patient to get their FBC result – but it’s less irksome than a patient dying from an ABO reaction.

The majority of WBIT incidents happen when bloods are taken by a doctor, during normal working hours.

c) The laboratory requests two samples taken at different times to mitigate against the risk of mis-labelling bloods. Taking both at the same time circumnavigates the very process designed to make it safer – it’s fine until it’s not fine – just like drunk driving is fine until it’s not fine.

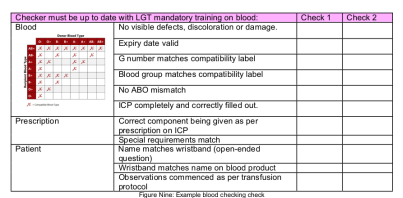

d) The bedside check of blood products should be done. In my trust, Nurses complete mandatory blood training which includes how to check blood. The Doctors don’t, although I have been trained a zillion years ago when I was an anaesthetic CT2. But what are we checking for?

9. The patient must be monitored during the transfusion.

Patients should be under regular visual observation and, for every unit transfused, minimum monitoring should include:

- Pre-transfusion pulse (P), blood pressure (BP), temperature (T) and respiratory rate (RR).

- P, BP and T 15 minutes after start of transfusion – if significant change, check RR as well.

- If there are any symptoms or signs of a possible reaction – monitor and record P, BP, T and RR and take appropriate action.

- Post-transfusion P, BP and T – not more than 60 minutes after transfusion completed.

- Inpatients observed over next 24 hours and outpatients advised to report late symptoms (24-hour access to clinical advice).

10. Education and training underpin safe transfusion practice.

And this is why we’ve written a blog for RCEMLearning!

References

- Information for patients about blood transfusion. Patient information leaflets. NHS Blood and Transplant.

- Patient information leaflets and video resources. Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCOA).

- The Strange Case of Penny Allison. YouTube uploaded by Patient Blood Management England, 18 Aug 2017.

3 Comments

Thanks a lot, I really like it

interesting read

Lots of information gained , thanks