Author: Nikki Abela / Editor: Liz Herrieven / Codes: SLO9 / Published 10/06/2019

June has come round again and it can only mean one thing: the Emergency Medicine Educator’s conference has come and gone and if you missed this year’s then you can follow it on twitter at #theEMEC and #EMECtap (Take Away Points). We have also recorded small podcast segments with most of the speakers and hopefully this blog will give you a flavour for what the day was like.

I have decided to talk in some detail here on the workshop I went to by Simon Carley, not because the other workshops or talks weren’t inspiring, but I do not feel I can do them all justice in this single blog, and because feedback is something which does not come naturally to me so I am hoping to be able to share this learning with you.

Sometimes during a high pressure environment, like the one we work in, it is really tempting to give (negative) feedback in the heat of the moment, but that may not be the best time or place for it. If you notice this happening to yourself or a colleague, take some time to pull them aside and ask them:

Then take some time away and ask yourself, is the feedback necessary? And when would be the right time, place, and person (with the right frame of mind) to do it?

To then demonstrate different forms of feedback and their effects on those receiving them, Simon led us in a game in which 3 volunteers were asked to leave the room and then come back in one at a time to find a hidden chocolate with the help of audience feedback.

The first person was given positive but useless feedback (e.g. “your shoes are really nice”), the second was given negative and non-specific feedback (e.g. “the other person found it by now”), and the last person was given positive and useful feedback (e.g. “it’s a really good idea that you’re looking in bags”). This was a really powerful demonstration on how, with the right type of feedback, you can pump someone up and help them achieve their goals, but also how unhelpful non-specific positive feedback can be and how demoralising it can be to be given negative feedback, even on something so abstract and useless like finding a chocolate in a workshop, in a conference in Birmingham. How much worse is it then to give negative feedback in a bad way on something so significant as outcomes in medicine?

This was really a take-home for me on the importance of improving how I feedback to learners and also about what I hope to achieve from feedback.

Simon broke this down into 3 things (taken from this book here):

- Appreciation (motivational feedback)

- Coaching (direction)

- Evaluation (expectation)

Remember that at any different point in time, trainees may be seeking to achieve different things from feedback (e.g. after a night shift, appreciation is likely the best form of feedback). However, whatever sort you are giving, be specific, make it meaningful and use the word “because”.

We need to be better at giving both positive and negative feedback, and we also need to be more comfortable at having difficult conversations.

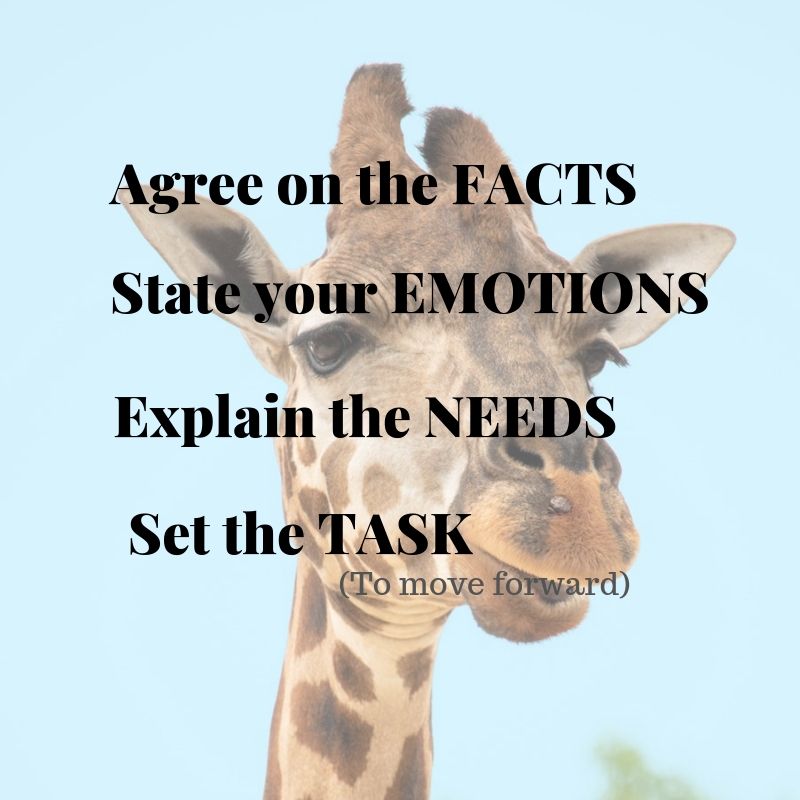

If you find this hard, think of the kindest and tallest animal on the plains of Africa, and give feedback in the form of the Giraffe technique:

St. Emlyn’s have a fantastic related post – you can read more here.

As always, the EMEC has been an inspirational conference for those hoping to be better at medical education, and if you want to hear more about what went on tune in to our podcasts in the next few months and follow it online if you can’t get yourself a ticket for next year.