Authors: Nikki Abela / Editor: Charlotte Davies, Liz Herrieven / Codes: EP6, IP1, SLO5 / Published: 08/12/2022

GAS – group A streptococcus/ Grp A Strep or GAS in short, is a common pathogen which can be found colonising respiratory tracts.

Many of us have been exposed to it or infected by it already. Those which haven’t, are likely to have either sub-clinical symptoms which self-resolve or may need a course of antibiotics following some moderate symptoms.

If it’s so common, why is it important now?

At the time of writing, there were 5 child deaths in the preceding 7 days due to invasive GAS (iGAS). Moreover, UKHSA reported an average of FOUR times increase in reported cases of Scarlet Fever and iGAS compared to average around the same time as the deaths (851 cases compared to an average of 186).

Why is this happening?

Alasdair Munro has a really good thread here and also has an excellent report here. Essentially I think this is because the under 5s, who this infection generally targets and tend to get infective symptoms from it (the rest of us have already been exposed), have spent a good proportion of their lives sheltered by the COVID-19 socially restricted pandemic. They are now being exposed to it for the first time, it is highly infectious and so it is being spread quite rapidly among this population group.

But why the invasive increase in infection rate?

GAS is an opportunistic pathogen. In the more serious diseases, preceding bacterial illness tends to be common.

So consider the usual viral rates for this time of year, add it to the increase due to social restrictions having lifted (and people being exposed to these pathogens for the first time), add in opportunistic bacteria and you have a recipe for disaster.

Because of this, PED attendances and primary care visits have now peaked – worried well and not so well are understandably worried that their children will contract this potentially deadly disease.

But what is it, really?

GAS actually is a normally found pathogen in the upper respiratory tract. However, in pathogenic cases it causes strep throat, scarlet fever, impetigo, toxic shock syndrome and cellulitis & necrotizing fasciitis.

Strep throat is something you need to think about if a child has a fever and sore throat. Petechiae on the palate, tonsillar exudates and cervical lymphadenopathy are thought to increase the chance that this is due to strep. Absence of cough and not much of a runny nose are also more in keeping with the disease.

In the current climate of looking at children’s throats so much, I thought I’d share this paediatric pearl, taught to me by Liz Herrieven about how to look at a (compliant) child’s throat without using a tongue depressor. Essentially challenge them to touch their tongue to their chin, as my cheeky monkey has demonstrated here. Use a torch of course, but feel free to have fun with the phrases – “I bet your tongue isn’t as long as mine – look I can touch my chin” is a good example.

Not terribly compliant? Then you need to master this hold described and video tutorial by Damian Roland here.

So many children present with fever or a sore throat at this time of

year, which ones should get antibiotics?

CENTOR criteria (modified for age) and FeverPAIN are scoring systems which can be used, but their performance in this age group isn’t great.

Some departments are now combining them with swabs to confirm or refute the need for antibiotics (as both the swabs and the scoring systems can not confirm with certainty whether the infection is caused by GAS, or not, the combined use may synergise their performance- although this needs to be proven still – I may be wrong).

Scarlet fever is also caused by GAS – it is characterised by fever, sore throat, a sandpaper like rash (get used to feeling it as it may be missed on non-white skin types – see Brown Skin Matters or DFTB Skin Deep if you want to get better at derm in non-white skin), and very red lips or tongue (strawberry tongue). Peeling of hands and feet is a late manifestation of this disease. DFTB have an excellent post on it here, which I highly recommend you read. EM3 also have a great lightening learning infographic.

Both Scarlet Fever and Strep Throat can generally be treated with a course of antibiotics – penicillin (for ten days in scarlet fever) being the first line (as it can be resistant to some second line antibiotics, some ID departments are advising to swab for sensitivities in those with a penicillin allergy). Although mild cases can resolve on their own, the current climate is in favour of treatment, to prevent spread and to prevent complications.

Once treated, the patient should remain isolated for 24 hours after starting antibiotic treatment to avoid spread.

When GAS causes scarlet fever, it is a notifiable disease.

Impetigo

Is a patch of erythema with crusts, usually found around the face and can cause cellulitis. It is generally harmless but needs treatment with topical or oral antibiotics depending on severity.

iGAS

When GAS invades the blood or deep tissue, it is classified as invasive GAS (iGAS), which is also a notifiable disease.

Apart looking out for sepsis, recent reports have shown an increase in respiratory cases associated with iGAS – like empyemas – so a low threshold for a CXR in children with GAS and respiratory symptoms or a prolonged fever would be appropriate.

There have also been reports of arthritis, nephritis and necrotising fasciitis.

In a clinically unwell child with symptoms of GAS/scarlet fever, and even without, in the current climate of enhanced infection rates (remember not everybody with the disease will know they have it), clinical vigilance with a period of observation and potentially biomarker guidance will help to guide decision making.

Needless to say, iGAS will need IV treatment with specialty/PICU referral.

Sometimes complications from GAS come about because of an increased immune response, causing diseases like glomerulonephritis and Rheumatic fever and treatment with antibiotics is thought to decrease the chances of this.

What about contacts?

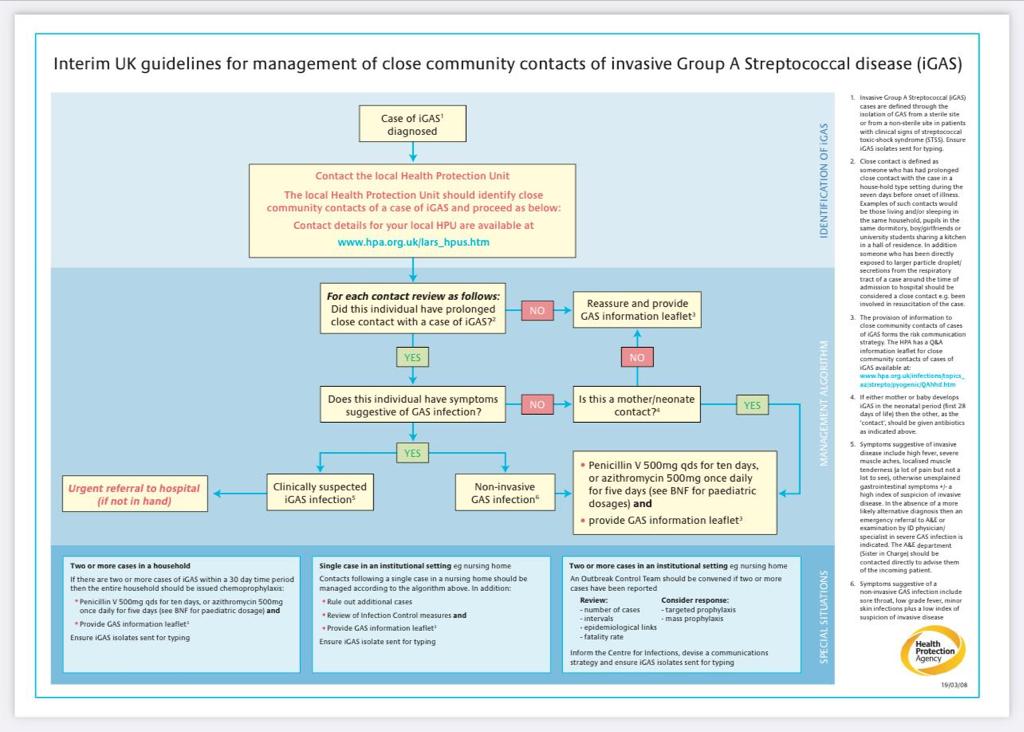

The Health Protection Agency have released the following guidance:

Other resources

If you are looking for patient resources, Damian Roland has a parent information video here.

The Alder Hey website has some patient info on their web page (which seems to have been used as a template for many school public health messages) and their symptom checker has a page on GAS and the healthier together website is another great starting point.

If your department has any patient information leaflets, posters or learning resources we can link here please get in touch or tweet us.

8th December 2022 update

RCEM, RCPCH and RCGP have also issued a joint statement here. In it they alert clinicians to think GAS, they also issue advise for parents when to see a GP/111/WIC and when to visit the ED.

Their statement hints that antibiotic shortage is on the horizon by encourage reporting of shortages here and linking to an advice video on how to teach children to swallow tablets – which may be something we may need to do soon.

A UKHSA update was also issued, giving an update on current stats:

“So far this season, there have been 85 iGAS cases in children aged 1 to 4 compared to 194 cases in that age group across the whole of the last comparably high season in 2017/2018. There have been 60 cases in children aged 5 to 9 compared to 117 across the whole of the last comparably high season in 2017/2018. The majority of cases continue to be in those over 45.

Sadly, so far this season there have been 60 deaths across all age groups in England. This figure includes 13 children under 18. In the 2017/18 season, there were 355 deaths in total across the season, including 27 deaths in children under 18.“

9th December 2022 update

Another multi-partnership report today, this time from NHS England, NICE, UKHSA, the Royal Pharmaceutical society, RCGP and RCPCH. The document is really easy to read and gives insightful advice, resources and teaching and is well worth a full read. Here are some of the updates:

GAS

- A low threshold for antibiotic prescribing in view of the current circulating levels of GAS and viral co-circulation “to children presenting with features of GAS infection, including when the presentation may be secondary to viral respiratory illness.”

- A low threshold for primary care to refer those with persisting/worsening symptoms

- Adjusted clinical decision rules, with a recommendation to prescribe antibiotics to children with a FeverPAIN score of 3 or more. (clinical judgement needs to be continued), given the current high prevalence of GAS

- Antibiotics: Pen V remains first line with amoxicillin, macrolides and cefalexin are alternative agents in decreasing preference (in the event of non-availability). Non severe penicillin allergy: macrolides with cefalexin as alternative. In severe penicillin allergy: macrolides remain the option of choice. Co-trimoxazole is an option in the event of macrolide non-availability and penicillin anaphylaxis.

- Duration of treatment: : “Five days of phenoxymethylpenicillin may be enough for symptomatic cure, but a 10-day course may increase the chance of microbiological cure”. In the current circumstances clinicians should be aware that a five day course will be appropriate for many children, at the discretion of the treating clinician.

iGAS

- Low threshold to consider pulmonary complications.

- Take a throat swab, blood cultures and other appropriate samples including respiratory culture, tissue and fluid samples.

- In the case of culture-negative fluid specimens, consider the use molecular diagnostics such as GAS-specific PCR or 16S rDNA PCR, as guided by microbiology specialists. Send all positive isolates (or DNA extract if molecular diagnosis only) to UKHSA reference lab for further typing and investigation.

There is also some excellent public health advice for schools and when they should be notifying UKHSA Health Protection Teams and how contacts of iGAS cases will be given prophylaxis and by whom.

Other RCEMLearning Resources

- Acute Sore Throat – Learning session

- Acute Sore Throat – Reference session

- Common Childhood Exanthems – Reference session

- Holiday sore throat – SAQ

- PANDAs and PANS – Neuropsychiatric Complications of GAS – Blog

- Paediatric Rashes – Blog

- A child with a fever – Blog

- Sore Throat NICE guidelines June 2018 – Podcast

7 Comments

Excellent, concise resource

Very nice and informative blog considering current situation. thank you

Very well explained. Useful for ED doctors. Thanks

Very helpful

Really concise, comprehensive and pragmatic, thank you

Very good, easy reading and explanation. Thank you.

Useful reading