Author: Janet Skinner / Editor: Adrian Boyle / Reviewer: Emma Everitt, Mohamed Elwakil / Codes: GC7, GP8, SLO1, SuC1, SuC13, SuC9, SuP6 / Published: 26/09/2022

This session will cover the diagnoses, management and treatment of anorectal conditions that commonly present to the Emergency Department.

Context

Patients with benign anorectal disease tend to present to primary care, although many present to the emergency department (ED), particularly when suffering from significant pain or rectal bleeding.

The common benign anorectal conditions that are going to be discussed in this session are:

- Haemorrhoids

- Anal fissure

- Anorectal abscesses, including pilonidal disease

- Rectal prolapse

However the spectrum of anorectal disease is broad and the differential diagnosis includes the perianal manifestations of many systemic diseases, including:

- Sexually transmitted infections

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Malignancy

Some other less common anorectal conditions that may occasionally present, are:

- Proctalgia fugax

- Anal cancer

- Proctitis

- Anorectal foreign bodies

- Anorectal area

Definition

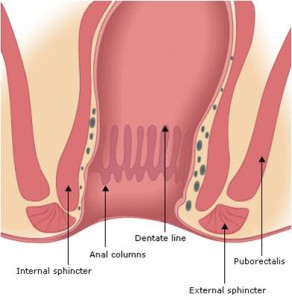

The anorectum is formed by the 12-15cm rectum and the 4cm anal canal. The columnar intestinal epithelium of the rectum changes to stratified squamous epithelium at the dentate or pectinate line, which is where the anal glands and crypts lie [1, 2].

The human anorectum

The anorectum is supplied by the haemorrhoidal arteries and drained by the internal haemorrhoidal plexus of veins. Sphincteric support is provided by the internal sphincter, puborectalis muscle and the external sphincter.

Anorectum detailing the internal sphincter, external sphincter and Puborectails

The external sphincter is made up of three parts:

- Deep

- Superficial

- Subcutaneous

and is a continuation of the puborectalis muscle.

Detailed int sphincter, anal columns, dentate line, ext sphincter and puborectais

These form a ring of muscle in the anus which have an important function in the maintenance of continence.

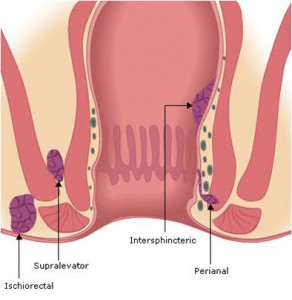

Several tissue spaces lie between the muscles and become sites of potential abscess and fistula formation [1, 2].

Learning Bite

Understanding the anatomy of the anorectal canal is vital in the assessment and management of patients with benign anorectal disease.

Haemorrhoids

Haemorrhoids are enlarged vascular cushions in the anal canal [3].

They can be classified as:

- Internal- occur above the dentate line

- External occur below the dentate line

They can also be classified in terms of their degree of prolapse, which helps to aid treatment decisions:

- 1st degree: completely internal

- 2nd degree: prolapse but reduce spontaneously

- 3rd degree: prolapse but reduce manually

- 4th degree: cannot be reduced once prolapsed[3]

Haemorrhoids

Other Anorectal Disease

anorectal abscess

Anal fissures

Are superficial tears of the anal mucosa [1]

Anorectal abscesses

Form a spectrum of disease that can affect various areas of the anorectum Fig1. The abscesses can be defined by their anatomic location

Pilonidal disease

Covers a spectrum of conditions from pilonidal sinuses, in the natal cleft to the formation of a laterally placed pilonidal abscess.

Rectal prolapse

Occurs when protrusion of all or part of the rectal canal takes place [4]

Basic Science and Pathophysiology

Haemorrhoids

The anal canal contains three fibro vascular cushions. It is thought that passing repeated hard stools and straining weakens the supporting tissues causing the cushions prolapse [1, 2]. These can become distended and engorged with blood causing the typical symptoms of haemorrhoids [3].

Haemorrhoids2

Anal fissure

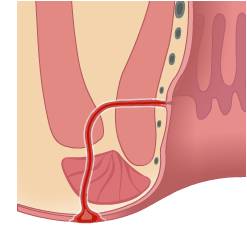

A superficial tear in the anal mucosa occurs when passing a hard stool. This normally occurs in the posterior midline as this is the point of maximum tissue weakness [1].

A sentinel pile or skin tag may occur at the distal end of the fissure [4].

Anal fissure

Anorectal abscesses

The anal crypts can become blocked Fig1 leading to abscess formation acutely (with Staph. Aureus as the commonest cause).

Chronic infection can lead to the development of a fistula Fig2. Blockage of a hair follicle in the natal cleft can lead to development of a pilonidal sinus. This sinus can become infected leading to chronic sinus inflammation, or formation of a pilonidal abscess that occurs laterally to the sinus [1, 2] [4]

History

Aspects of the history can help to differentiate between the various anorectal pathologies as shown in the table Fig1.

Other symptoms include:

- Itch

- Discharge

- Swelling

with external haemorrhoids or rectal prolapse.

| PAIN | BLEEDING | |

| Haemorrhoids | Normally painless, unless thrombosed [3] | Tend to cause bright red blood on stool or pan [1, 2] |

| Anal Fissure | Severe pain on defecation lasting for 1-2 hours after [5] | Tend to cause small amount of bright red blood on paper [1, 2] |

| Anorectal abscess | Pain worse on defecation or sitting, a tender swelling, deep pain or buttock pain depending on location of absces [1] | Small amounts of blood or pus PR may occur if fistula present |

| Rectal prolapse | Largely painless unless strangulated | Blood stained mucus PR [4] |

Questions

It is vital to ask about systemic symptoms, including, weight loss and fever. These can suggest a systemic disease with anorectal manifestations e.g. inflammatory bowel disease, particularly Crohns disease.

Recurrence can also indicate an underlying medical condition such as diabetes, carcinoma or immunosuppression e.g. HIV. Multiple fissures and fistula formation also suggest an underlying systemic cause [4].

Always ask about altered bowel habit and take a sexual history.

Sexually transmitted infections that have anorectal manifestations include; chlamydia, herpes, syphilis and condylomata acuminata (anogenital warts) [1, 2]

Learning Bite

Taking a clear and detailed history and maintaining a high index of suspicion for systemic diseases is important in diagnosing anorectal conditions in the ED.

Examination

PR Exam

When carrying out the examination note the following points:

Inspection of area this should be carried out in a well-lit area with the patient in the left lateral position. Look for obvious abscess or areas of induration or pain to suggest a deeper abscess.

Note any external haemorrhoids (including degree) or anal fissure (presence of a sentinel pile hints to ward a fissure). Assess appearance of any haemorrhoids (purplish tender grape like haemorrhoids tend to be thrombosed, black haemorrhoids tend to be necrotic). Always look in the natal cleft for the presence of any pilonidal sinuses.

Digital rectal examination Will often be normal if patient has haemorrhoids, often painful and poorly tolerated if they have an anal fissure or abscess!

Proctoscopy /anoscopy Must be performed, although depending on local protocols this may be performed by the surgical team either in the ED or in a follow up out-patient clinic. Haemorrhoids will appear at 3,7,11 oclock when the patient is supine [3]

Anorectal Obscesses

This table details the location of anorectal abscesses, how commonly they present in these areas and an overview of the patients symptoms.

| Location | Frequency | Symptoms |

| Perianal | 40% | Pain and fluctuant swelling at anal verge |

| Ischiorectal | 20% | Buttock pain and induration, may be no swelling |

| Intersphincteric | 20% | Rectal fullness on PR |

| Supralevator | 5% | Buttock and rectal pain, little external evidence of |

Learning Bite

a significant number of anorectal abscesses will show subtle or little external evidence so a high index of suspicion must be maintained in a patient with buttock or anorectal pain.

Risk Assessment

There are no risk assessment tools to predict morbidity and mortality in patients with benign anorectal disease. The degree of haemorrhoidal prolapse can be used to determine treatment.

As with all abdominal conditions, the presence of haemodynamic instability indicates a patient at risk of a poor outcome.

- Resuscitate any patient with signs of sepsis or haemodynamic instability

- Involve senior ED physician

- High concentration oxygen delivered via a variable deliver mask with reservoir bag

- Two large bore peripheral intravenous cannulae

- Bloods

- Intravenous fluids crystalloid administer 1-2 litres immediately and reassess

- IV broad spectrum antibiotics if signs of sepsis

- Urinary catheter and measure urine volumes

- Urgent referral to senior Surgeon and Critical Care

- Analgesia as required

- Patients that do not require urgent surgical intervention can generally be discharged for either GP or surgical follow up.

Haemorrhoids

Most patients can be discharged to either GP care or with surgical follow-up; some patients may require urgent surgical referral or admission, these include:

- Patients with profuse haemorrhoidal bleeding [4]

- Thrombosed haemorrhoids although these are acutely painful most patients can be treated conservatively at home with analgesia, ice, bed rest, stool softeners. Symptoms usually settle within 2 weeks [3]

- If the external haemorrhoid is necrotic or gangrenous then surgery may be needed to excise the haemorrhoid [4, 7]

- Patients with 4th degree haemorrhoids (NHS)

- Suspected malignancy (NHS)

Anal fissure

Patients can normally be discharged home with analgesia, stool softeners and surgical follow-up.

Anorectal abscesses

All require surgical intervention. There is no role for the treatment of a closed abscess with antibiotics, incision and drainage is required and failing to ensure that this happens in a timely fashion risks worsening sepsis, fistula formation and serves only to delay surgery.

Rectal prolapse

All should be referred to the admitting surgical team [4].

Systemic causes

Should be admitted or followed up by the appropriate speciality e.g. Genito- Urinary Medicine for suspected STDs.

Learning Bite

Most patients with anorectal conditions, except abscesses, can be managed as out patients.

Medical Therapy

Medical management of anorectal conditions:

Haemorrhoids

A meta-analysis supports use of early fibre supplements to improve symptoms and to prevent straining [3].

Also good anal hygiene is important.

There is widespread use of topical local anaesthetic and steroid creams although little evidence to support their use and they may be harmful in the long term [3].

The WASH regimen (Warm water, Analgesics, Stool softeners, and a High-fiber diet with fiber supplements) can provide relief from non-thrombosed external hemorrhoids.

Anal fissure

The pain is normally due to spasm of the internal sphincter rather than the actual fissure [5] so theoretically anything that can reduce spasm should promote healingGTN ointment is generally used as a first line treatment with good success, although recent trials have shown healing rates no greater than placebo injections.

Calcium channel blockers may be a promising future treatment with less side effects (such as headache) than GTN [5, 9].

Anorectal abscesses

All require surgical intervention.

Adjunctive antibiotics are normally only needed if the abscess is complicated, deep, associated with cellulitis or the patient is immunocompromised [1]

Pilonidal disease

The presence of a pilonidal sinus, without abscess formation can benefit from good hygiene and the shaving of hairs in the natal cleft which both promote healing[4]

Learning Bite

There is little firm evidence to support medical therapies in anorectal conditions except fibre supplements in the management of haemorrhoids.

Surgical Therapy

Surgical management of anorectal conditions:

Haemorrhoids

Rubber band ligation as an out-patient is effective and will relieve symptoms in 80% of 1st, 2nd and 3rd degree haemorrhoids [3].

Haemorrhoidectomy

Is reserved for 4th degree or failure of conservative therapy-open v closed technique. Traditional excision haemorrhoidectomy is still more effective in terms of recurrence rates than newer stapled techniques [3, 10].

Anal fissure

Sphincterotomy is effective in 90% although 10% of patients will develop long term incontinence, anal stretch results in higher rates of incontinence [5, 11].

Anorectal abscesses

All require surgical drainage and this should normally be carried out under general anaesthesia in the operating room. In some centres, mainly in the US, superficial abscesses are drained in the ED [1]

Pilonidal abscesses

Should be incised off midline [1]

Sinuses should be fully excised once the abscess has settled. Pilonidal sinuses (AND ANORECTAL FISTULAS) heal best with primary closure after excision [12].

Rectal prolapses

Excision is normally combined with pelvic floor repair [4].

- Treating significant anorectal abscesses with antibiotics rather than incision and drainage will be unsuccessful and delay definitive management.

- Failing to investigate patients aged 40 years or more with PR bleeding will miss anorectal carcinomas/malignancy.

- Beware the patient with rectal pain and no apparent abnormality; they may have a serious deep abscess. A CT scan should be obtained.

- Recurrent anorectal conditions suggests an underlying systemic disease.

- Maintain a high index of suspicion for systemic diseases presenting with anorectal manifestations

- All patients must have a digital rectal examination and proctoscopy performed

- Most patients can be managed conservatively and safely discharged with appropriate follow-up arranged

- Fibre supplements are beneficial in the early treatment of haemorrhoids (grade 3a. recommendation B)

- Most haemorrhoids can be managed with rubber band ligation with surgery reserved for 4th degree or after failure of ligation (Grade 3a, recommendation B)

- All anorectal abscesses require surgical drainage

- Topical therapies, such as, nitrates are being increasingly used in the conservative management of anal fissures (grade 3a, recommendation B)

- Coates WC. Anorectum. In: Wall R, Hockberger R, et al. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 10th edn. Elsevier. 2022.

- Burgess BE, Bouzoukis JK. Anorectal disorders. In: Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS et al, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 6th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003.

- Acheson A G, Scholefield J H. Management of haemorrhoids BMJ 2008; 336 :380.

- Dunlop M. Anorectal conditions. In: Garden OJ, Bradbury AW, Forsythe JLR et al, eds. Principles and Practice of Surgery. 5th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2007:332-340.

- Nelson RL. Treatment of anal fissure. BMJ. 2003 Aug 16;327(7411):354-5.

- Greenhalgh R, Cohen C R, Burling D, Taylor S A. Investigating perianal pain of uncertain cause. BMJ 2008; 336 :387

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Haemorrhoids. NICE CKS. Revised: 2021.

- Alonso-Coello P, Guyatt G, et al. Laxatives for the treatment of hemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Oct 19;2005(4):CD004649.

- Nelson RL, Thomas K, Morgan J, Jones A. Non surgical therapy for anal fissure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Feb 15;2012(2):CD003431.

- Lumb KJ, Colquhoun PH, et al. Stapled versus conventional surgery for hemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Oct 18;2006(4):CD005393.

- Nelson RL, Chattopadhyay A, Brooks W, Platt I, Paavana T, Earl S. Operative procedures for fissure in ano. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Nov 9;2011(11):CD002199.

- McCallum I, King PM, Bruce J. Healing by primary versus secondary intention after surgical treatment for pilonidal sinus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD006213.

7 Comments

Goog consice summary of assessment and management of anorectal conditions likely to present to the ED

Good revision overview of anorectal disease

concise and very useful

Good and informative review on PR bleeding!

the grade of evidence for each treatment was very helpful. I have to admit I don’t go in to see a patient with anorectal disease thinking about sexually transmitted diseases as a possible cause, but this teaching session helped mebroaden my perspective

very well presented.

I was alway told to try abx first then if that does not work for surgery, this will change my practice. Thank you