Author: Alexis Leal / Editor: Januaryet Skinner / Reviewer: Isabelle Hancock, Raja Shahid Ali / Codes: ACCS LO 2, GC5, GC7, GP8, HP3, RP7, SLO3, SuC13, SuC8, SuC9, SuP5, SuP6 / Published: 07/10/2022

Context

Acute lower GI haemorrhage accounts for approximately 20% of all cases of GI haemorrhage and is a frequent cause of hospital admission [1-3].

It usually causes less haemodynamic instability than upper GI haemorrhage, however, it can present as a wide spectrum from trivial bright red blood per rectum to massive haemorrhage with shock. As such, the bleeding can be catastrophic and should be considered as a potential surgical emergency, with mortality rates reportedly as high as 21% in those with massive GI haemorrhage*[4].However, in the majority of cases bleeding stops during initial resuscitation, allowing time for further investigations to elicit the exact source and cause of bleeding, with an overall mortality rate of around 2-4% [5-9].

*Massive Haemorrhage implied in this study if: large volumes of blood passed, 2+ units of RCC required or Haemodynamic instability.

Definition

Lower GI bleeding is defined as bleeding distal to the ligament of Treitz (i.e. some of the small bowel, the colon and the rectum) which presents with the passage of bright red blood per rectum (haemotochezia) without the presence of blood in gastric aspirate.

Acute lower GI bleeding is of recent onset and may be severe, resulting in haemodynamic instability and decreasing haemoglobin levels. The diagnosis is often difficult to make and may require multiple investigations to identify the source of bleeding.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of lower GI haemorrhage can best be understood by looking at the potential causes [10].

These include:

- Diverticular disease

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Neoplasia

- Benign anorectal disease

- Angiodysplasia

- Others

Diverticular disease

The most common cause of lower GI bleeding involves the colonic diverticular, with diverticulosis as the source of bleeding.

It is uncommon in those under the age of 40 years but there is more than a 200 fold increase from the age of 20 to 80 years [11]. It has been shown that asymmetric rupture of the vasa recta at the dome of the diverticulum with intimal eccentric thickening and medial thinning can be found at or near the bleeding point. Trauma is thought to play a role in predisposing the diverticula to bleed [11,12].

Learning bite

Diverticular disease is the commonest cause of acute lower GI haemorrhage in the elderly.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease & Colitis

Inflammatory bowel disease includes:

- Ischaemic colitis

- Ulcerative colitis

- Crohn’s disease

- Infective colitis

Ischaemic colitis is the most common form of intestinal ischaemia and in most cases is transient and reversible. The colon is predisposed to ischemic insult due to its poor collateral circulation, low blood flow and high bacterial content with the splenic flexure, recto-sigmoid junction and the more frequent involvement of the right colon.

This diagnosis should be considered in patients presenting with abdominal pain and bloody diarrhoea.

Older adults are most likely to experience ischemia-related colitis because of underlying risk factors such as relative hypotension, heart failure, and arrhythmias [13].

A simple stool culture could reveal infective causes such as Salmonella, Shigella and Campylobacter.

Neoplasia

Neoplasia (both carcinoma and polyps) can produce acute lower GI haemorrhage, although this more commonly presents with occult blood loss.

Colorectal cancer is common in the UK and a frequent cause of cancer deaths. Incidence increases with age and a family history of bowel carcinomas is common.

As well as rectal bleeding, left sided large bowel carcinomas frequently cause altered bowel habit and abdominal pain.

Other causes of rectal bleeding (such as colitis) can predispose patients to developing neoplastic lesions.

Learning bite

A digital rectal examination can save lives by identifying a rectal carcinoma.

Benign Anorectal disease

Anal fissures can present with small amounts of fresh PR bleeding (often seen on toilet paper after wiping). They can be associated with severe pain which is worse on defecation, normally due to the passage of a hard stool tearing the anal lining. Pain results in spasm of the sphincter, often making PR examination impossible. However, if the fissure is visualised it is usually seen in the posterior mid line.

Haemorrhoids are the most common cause of rectal bleeding in those under 50 years of age [13]. Patients with haemorrhoids typically present because of one of three complications:

- Haemorrhage

- Prolapse

- Thrombosis

With regard to bleeding, it is usually fresh and onto the surface of the stool. It is normally self-limiting and is rarely life threatening.

Learning bite

Benign anorectal conditions normally cause minor or self-limiting bleeding.

Angiodysplasia

Angiodysplasia is another cause of acute lower GI haemorrhage and is an acquired malformation of intestinal blood vessels with ectatic vessels in the mucosa and submucosa. Dilated vessels or cherry red, flat lesions are seen at colonoscopy.

Angiodysplasia most commonly presents with iron deficiency anaemia and occult blood loss. This is due to slow but repeated episodes of bleeding (often found in asymptomatic individuals or as an incidental finding.

When overt bleeding from angiodysplasia occurs it is typically brisk, painless and intermittent.

Other causes

Other causes of lower GI bleeding include:

- Radiation injury

- Meckel’s diverticulum

- Other small bowel pathology

- Solitary rectal ulcers

- Portal colopathy

- Prostate biopsy sites

- Dieulafoy lesions

- Endometriosis

- Colonic varices

Ten to fifteen percent of patients with an apparent lower GI bleed will, in fact, have an upper GI source for their bleeding (see image below) [6].

Learning bite

Bleeding oesophageal varices or peptic ulcer disease can present with fresh blood PR.

History

All patients with a suspected acute lower GI bleed should be assessed as a matter of some urgency, as there can be significant mortality (up to 20%). [1,2,3]

A thorough history and examination are essential in order to:

- Try and help identify the source of bleeding

- Make some assessment as to the amount of bleeding which may have occurred

- Ensure adequate resuscitation is instituted

Patients who present with acute lower GI haemorrhage often find it difficult to describe and may complain of passing bright red blood per rectum. It is useful to clarify the exact nature of the blood by the frequency, colour and the presence or absence of clots.

Melaena (dark tarry stool) generally indicates an upper GI or small bowel source, whereas fresh, red blood generally indicates bleeding from the left colon or rectum. However, it is important to remember that this is not always the case.

Other symptoms

Other symptoms (such as fatigue, chest pain, palpitations and shortness of breath) should be elicited along with any past medical history.

Certain symptoms may help to distinguish between inflammatory, infective and malignant causes, such as abdominal pain, weight loss, fever, diarrhoea or vomiting.

Medication use is also of relevance. In particular, the use of warfarin, heparin, NSAIDS and inhibitors of platelet aggregation can be important as some of these medications may require urgent reversal.

Physical Examination

A thorough physical examination is important to assess the amount of blood loss, the degree of shock and the possible source. It is important also in identifying any other medical conditions which may play a role in the morbidity and mortality, and potentially affect future investigations.

Initial observations (such as dyspnoea, tachypnoea, tachycardia and, in particular, postural drop in blood pressure) are important and may indicate more significant blood loss and shock.

The presence of abdominal tenderness on examination may help to suggest that the source of bleeding is more likely to be secondary to an inflammatory disorder, such as ischaemic colitis.

A PR examination must be performed in all those suspected of GI haemorrhage (not only to assess the stool colour, presence of blood and so on, but also to look for anorectal lesions).

Identify Haemodynamic Instability

If there is any evidence of haemodynamic instability then involve a senioremergency department physician and institute the following resuscitative steps:

- High concentration oxygen delivered via a variable deliver mask with reservoir bag

- Two large bore peripheral intravenous cannulae

- Bloods (see investigations)

- Large IV access should be obtained urgently

- Consider if major haemorrhage protocol needs to be activated if hemodynamically unstable and visibly excessive blood loss PR.

- Following your local blood transfusion protocol should result in appropriate amounts of RBC, FFP and plasma.

- Increments of fluids and blood products dependent on patients age, estimated blood loss, and blood availability should be used to maintain adequate vital signs [14,15]

- Gastric tube and aspirate stomach if in doubt about the upper GI source

- Urinary catheter and measure urine volumes

- Urgent referral to senior surgeon and critical care if instability persists

Learning bite

Prompt resuscitation and early involvement of surgical team are vital.

Assessment of Severity

BLEED Classification System

B – ongoing Bleeding,

L – Low systolic blood pressure

E – Elevated prothrombin time

E – Erratic mental status

D – unstable comorbid Disease.

There is extensive literature regarding risk stratification of upper GI bleeds, such as the Rockall score which is well validated and widely used. However, there is little information available in the literature for risk stratification of lower GI bleeds.

As most episodes of lower GI bleeding settle spontaneously, the early identification of high risk patients will allow for a more selective delivery of urgent therapeutic interventions.

One study developed the BLEemergency department classification system which allows the triage of patients into high or low risk groups of adverse in-hospital outcome (recurrent haemorrhage, need for surgery to control bleeding and death) [12].Another study developed the BLEED classification system [1]. Any patient with any of the criteria in tables above were deemed to be high risk.

Note none of these classification systems are well validated or in common use

Learning bite

Despite the fact that there is no well validated risk classification system, any patient with haemodynamic instability is at high risk for severe bleeding.

National Guidelines

Despite the low quality of evidence, the American College of Gastroenterology advises using the risk factors from these studies to help distinguish patients at risk. Risk factors of poor prognosis mentioned include: being elderly, those with co-morbidities, on aspirin & those presenting with low BP/HR. [13]

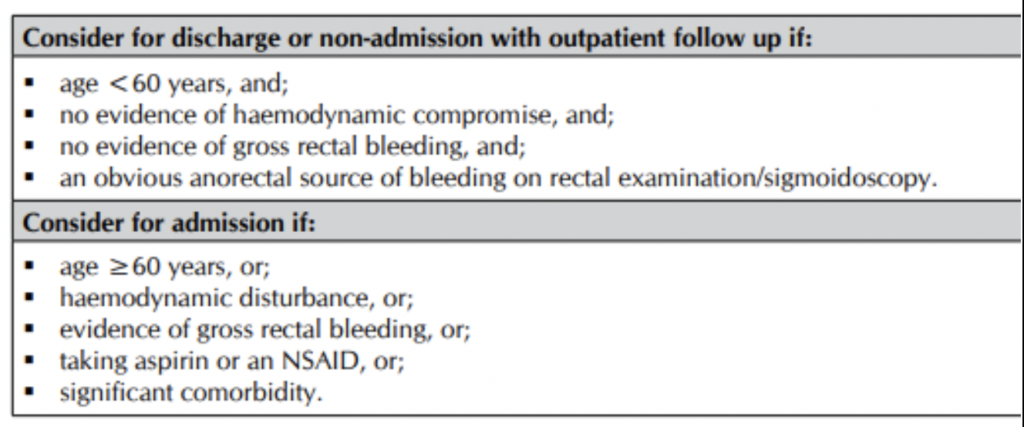

The Scottish National Guidelines committee have also issued clear guidance for admission in the following table below: [16]

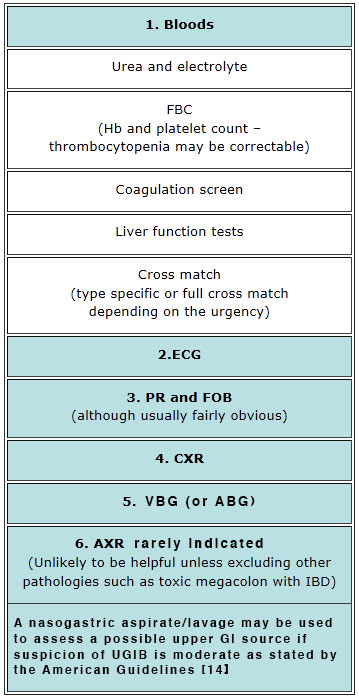

As with most things seen in the emergency department initial assessment and resuscitation should coincide. Investigations are shown in the table below.

The majority of patients with lower GI haemorrhage will stop bleeding during initial resuscitation allowing investigation of the source of bleeding to proceed as an in-patient. This is the source of some controversy and may well depend on local policy or on an individual case decision. The likelihood of locating the abnormality, the potential complications of the investigation and the further treatment options that the investigation allows all need to be considered when deciding which investigation is the most appropriate.

As with most things seen in the emergency department, initial assessment and resuscitation should coincide.

The majority of patients with a lower GI haemorrhage will stop bleeding during initial resuscitation, allowing investigation of the source of bleeding to proceed as an inpatient.

The likelihood of locating the abnormality, the potential complications of the investigation and further treatment options will all need to be considered when deciding which investigation is the most appropriate.

Introduction

-

- Unlike other clinical conditions, the investigation and definitive treatment of lower GI haemorrhage is often carried out at the same time.

The image opposite shows the steps to take in the management of an acute GI bleed.

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy has an established low morbidity and mortality and a yield of 72% to 86% [5]. It also allows certain treatments to be carried out at the same time.

Guidelines published by the American Society for Gastroenterology strongly recommend that Colonoscopy should be the initial diagnostic procedure for nearly all patients presenting with acute LGIB. In patients with high-risk clinical features and signs or symptoms of ongoing bleeding, a rapid bowel purge should be initiated following hemodynamic resuscitation and performed within 24 h of patient presentation [13].

A limitation of this investigation, however, is the difficulty in visualising the mucosa during or soon after a bleed (making it difficult to accurately identify the bleeding site).

During colonoscopy, it is possible to perform coagulation to stop the bleeding (thermal contact or epinephrine injection), particularly for AVMs. However, it is vital to consider the risk of perforation when using this treatment modality. Other treatments available at colonoscopy include haemoclips and band ligation [16].

Learning bite

Colonoscopy is the investigation of choice in most patients with lower GI bleeds.

Angiography

Angiography is thought to be preferable in those with a massive haemorrhage, but success rates in identifying the source of bleeding vary from 40% to 85% depending on the cause of bleeding [17, 18].

The source of bleeding is identified by visualising extravasation of contrast material into the lumen of the bowel.

Superselective embolisation aims to decrease the arterial blood flow. This reduces pressure to the bleeding site so haemostasis occurs. There is a small risk of ischemia

It is recommended by NCEPOD that Hospitals have a duty of care to provide acute haemorrhage control. Those that do not provide on-site IR should liaise with their regional centre to establish an agreed formalised network [19].

Learning Bite

Angiography is recommended in patients with a massive lower GI haemorrhage or if a colonoscopy proves unsuccessful.

Other Investigative Options

Other investigative options include:

- Proctoscopy

- Technetium labelled red blood cell scanning

- Upper GI endoscopy (shown opposite)

- CT angiography

- Recto-sigmoidoscopy

Learning bite

The SIGN guidelines state that all patients with rectal bleeding should undergo proctoscopy [15].

Medical Therapies

Unlike in upper GI bleeds, where IV vasopressins and proton pump inhibitors have an accepted role in the management of patients, there is little use for medical therapies in patients with lower GI bleeds.

Treat those patients taking warfarin in line with local protocols. Low dose aspirin is usually continued and NSAIDS stopped. Consider if the risk of re-bleeding outweighs need to be on anticoagulant, this may involve a discussion with appropriate specialty [20].

Learning bite

There is little role for medical therapies in the management of lower GI haemorrhage.

Surgery

Most patients have intermittent bleeding, or the bleeding can be controlled with non-surgical therapies. However, a minority may need to undergo surgery. In the national LGIB audit in 2018, only 117/2528 (4.6%) admitted patients underwent surgery [14].

Where possible, accurate pre-operative localisation of the bleeding site is essential to allow successful segmental resection, if not, a high rate of re-bleeding is likely. When surgery is required before any investigations are able to be undertaken, it is important to try and diagnose the bleeding point intra-operatively. When this is not possible, a subtotal colectomy is often performed.

Surgery acutely for LGIB should be considered if massive bleed, and after other therapeutic options have failed. One should take into consideration the extent and success of prior bleeding control measures, severity and source of bleeding, and the level of comorbid disease [13].

Ideally accurate pre-operative localisation of the bleeding site is essential to allow successful segmental resection, if not, a high rate of re-bleeding is likely. When surgery is required before any investigations are possible, it is important to try and diagnose the bleeding point intra-operatively. When this is not possible, a subtotal colectomy is often performed.

The image shows an anterior resection.

Learning bite

Surgery acutely for LGIB is rarely required (<5%) and should be considered after other therapeutic options have failed [14].

Low Risk GI Bleeds

Patients with benign anorectal causes of lower GI haemorrage can often be managed as an outpatient.

Patients with anal fissures can normally be discharged home from the emergency department with adequate analgesia, advice regarding diet and water intake or faecal softening agents.

Patients with haemorrhoids (if otherwise stable) can usually be safely discharged home from the emergency department with faecal softening agents. However, they may need further investigation to rule out a more sinister cause for bleeding which will be indicated by the patient’s age, other history and physical findings on examination. These investigations, however, can often be performed as an out patient.

Learning bite

These patients must all have a digital rectal exam (strong recommendation) [15].

- Diverticular disease accounts for 40% of significant lower GI bleeds

- In most cases of lower GI haemorrhage the bleeding will stop spontaneously allowing further investigations to be carried out as an in-patient

- Although the mortality of acute lower GI bleeds is low (about 2-4%), bleeding can be catastrophic with mortality as high as 20% in the case of massive haemorrhage

- There is no commonly used risk scoring system in patients with lower GI haemorrhage but patients with haemodynamic instability (particularly after initial resuscitation) are at high risk of poor outcome (Grade 2b, recommendation D) (1,14)

- Some low-risk patients with minor bleeds secondary to benign anorectal disease may be discharged after ED assessment (Grade 4, recommendation D)

- Prompt fluid resuscitation, early surgical review and involvement of critical care is the key to the management of unstable GI bleeds in the ED (Grade 4, recommendation D)

- None of the various treatment options necessarily prevent rebleeding (Grade 3, recommendation D)

- Colonoscopy performed in an emergency (within 24 hours of admission) is safe and effective (Grade 2b, recommendation D)

- Surgical intervention is required when haemodynamic instability persists despite aggressive resuscitation or bleeding continues/recurs (Grade 3, recommendation D)

It is important to be aware of the following pitfalls when dealing with the assessment and management of lower GI haemorrage:

- Underestimating the severity of bleeding can have dire consequences

- Failure to comprehend that even with treatment there is a relatively high rate of rebleeding

- Forgetting that up to 15% of patients with fresh PR bleeding will have an upper GI source and the cause of bleeding may only be found on an upper GI endoscopy

- Failure to recognise that haemodynamic instability, particularly following initial resuscitation, indicates a high risk patient at risk of significant bleeding and higher complication rates

- Failure to perform a digital rectal examination in patients with a lower GI bleeding (this must be done in all patients)

- Kollef MH, O’Brien JD, Zuckerman GR, Shannon W. BLEED: a classification tool to predict outcomes in patients with acute upper and lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 1997 Jul;25(7):1125-32.

- Peura DA, Lanza FL, Gostout CJ, Foutch PG. The American College of Gastroenterology Bleeding Registry: preliminary findings. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997 Jun;92(6):924-8.

- Velayos FS, Williamson A, Sousa KH, et al. Early predictors of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding and adverse outcomes: a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004 Jun;2(6):485-90.

- Billingham RP, The conundrum of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Surgical Clinics of North America. 1997 Feb:77(1): 241-252

- Jensen DM, Machicado GA. Diagnosis and treatment of severe hematochezia. The role of urgent colonoscopy after purge. Gastroenterology. 1988 Dec;95(6):1569-74.

- Jensen DM, Machicado GA. Colonoscopy for diagnosis and treatment of severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Routine outcomes and cost analysis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997 Jul;7(3):477-98.

- Leitman IM, Paull DE, Shires GT 3rd. Evaluation and management of massive lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Ann Surg. 1989 Feb;209(2):175-80.

- Longstreth GF. Epidemiology and outcome of patients hospitalized with acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997 Mar;92(3):419-24.

- Farrell JJ, Friedman LS. Review article: the management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005 Jun 1;21(11):1281-98.

- Vernava AM, Longo WE, Virgo KS. A nationwide study of the incidence and etiology of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Surg Res Commun 1996;18:113-120.

- Meyers MA, Alonso DR, Gray GF, Baer JW. Pathogenesis of bleeding colonic diverticulosis. Gastroenterology. 1976 Oct;71(4):577-83.

- Meyers MA, Alonso DR, Baer JW. Pathogenesis of massively bleeding colonic diverticulosis: new observations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976 Dec;127(6):901-8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.127.6.901.

- American Collage of Gastroenterology (ACG) Clinical guideline. Lower GI bleeding. 2016.

- Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (National Comparative Audit of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding and the Use of Blood. Results from a National Audit. 2016.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Blood transfusion. NICE Guideline [NG24] November 2015.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) Management of acute upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding, National Clinical Guideline 105, September 2008.

- Longstreth GF. Epidemiology and outcome of patients hospitalized with acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997 Mar;92(3):419-24.

- Khanna A, Ognibene SJ, Koniaris LG. Embolization as first-line therapy for diverticulosis-related massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding: evidence from a meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005 Mar;9(3):343-52.

- National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD). Time to get control? A review of the care received by patients who had a severe gastrointestinal haemorrhage. July, 2015.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in over 16s: Management. NICE [CG 141] June 2012. Last updated: August 2016.

19 Comments

it is an excellent learning module

excellent learning module

very useful

Excellent learning bite

very comprehensive

Very useful

Excellent , Thanks

very useful

v good

excellent module, common presenting complaint

good topic

Excellent revision on LGIB.

good revision

very good learning module

very informative module

Very helpful

Very useful!

Very good teaching covering the full spectrum of LGIB possibilities

Excellent article