Author: Henry R Guly / Editor: Jason Kendall, Amanda King / Reviewer: James Waiting, Amanda King / Code: ELC5, ElC6, ELC7, ELP2, ELP3, ELP4, SLO4, TC2, TP6, TP7 / Published: 05/03/2021

Fractured neck of femur is an important injury for many reasons:

- It is common

- It can be difficult to accurately diagnose

- Its incidence is increasing

The majority of fractures are caused by falls in the elderly and the fracture usually occurs through osteoporotic bone.

Patients who fracture their neck of femur commonly also have multiple co-morbidities which contributes to the high mortality rate associated with this injury. Multi-disciplinary care is key to the acute and chronic management of this cohort of patients during their hospital admission, and many hospitals have dedicated pathways to ensure patients receive the best care possible.

Emergency physicians do not need to know details of the surgical management of this condition but need to know enough about the principles of management to advise patients and their relatives about the likely treatment and outcome.

This review is based largely on two evidence-based guidelines by the British Orthopaedic Association (BOA) [1] together with other groups in 2007 and by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) in 2009. [2] There are NICE guidelines on falls [3] and on thromboprophylaxis [4].

Risk factors

The risk factors for a fractured NOF can simplistically be divided into:

- Falls

- Osteoporosis

Note however that there are some things, such as alcohol or immobility, which may be risk factors for both.

Osteoporosis can be classified as:

- Primary

- Type 1 (post menopausal)

- Type 2 (senile) age-related osteoporosis which occurs in males and females

- Idiopathic

- Secondary

- Endocrine: eg Cushings syndrome, thyrotoxicosis, hypogonadism, hyperparathyroidism

- Gastrointestinal eg malabsorption

- Drugs eg corticosteroids, long term heparin

Risk factors for osteoporosis include:

- Age >65

- Inactivity

- Current smoking

- Excessive alcohol intake

- BMI <18.5

- Heredity.

A patient who has had one osteoporotic fracture doubles their risk of a further fracture.

Not all fractures are caused by osteoporosis: other causes of hip fractures include:

- Metastases

- Pagets disease

- Osteomalacea

- Hyperparathyroidism

Risk factors for falls include:

- Muscle weakness

- Abnormalities of gait or balance

- Neurological disease eg Parkinsons disease, stroke

- Poor visual acuity

- Drug therapy: sedatives, hypnotics, diuretics, antihypertensives

- Alcohol

Prevention

A Cochrane Review suggests that the following are likely to be beneficial in preventing falls. [5]

- Multidisciplinary, multifactorial health/environment risk factor screening and intervention programmes

- Muscle strengthening and balance retraining

- Home hazard assessment and modification

- Withdrawal of psychotropic medication

- Cardiac pacing in patients with cardioinhibitory carotid sinus hypersensitivity

- A 15 week Tai Chi group exercise intervention

It also suggests that brisk walking is unlikely to be beneficial.

Controversially to the Cochrane review, new evidence has suggested that even when number of falls are reduced, there is a lack of evidence that fractures are also reduced [5].

Bisphosphonates have been shown to increase the bone density in the hips and to reduce the incidence of hip fractures.

Calcium, vitamin D and hormone replacement therapy have been shown to reduce the incidence of fractures.

Assessment

All patients with a fragility fracture should be assessed for both osteoporosis and for the risk of future falls. Appropriate interventions should then be instituted [1].

Any older person that presents to the emergency department following a fall, should be screened for risk factors for future fragility fractures. This is a combination of clinical examination, history and risk-assessment, in addition to simple measurements such as postural BP, and where appropriate the patient should be referred to a dedicated falls outpatient clinic.

Diagnosis of the cause of the fall

Patient history: It is important to ascertain the mechanism behind a patients fall, so clinical assessment should focus on identifying any preceding symptoms. The term ‘mechanical fall’ is not favoured amongst teams who care for elderly patients regularly as it does not accurately characterise the nature of a fall. Important causes including cardiac dysrhythmia, postural hypotension and infection should not be missed. There is not always history of a fall. Sometimes there has been a fall that the patient cannot remember (e.g. as a result of dementia) or describe (e.g. due to dysphasia). However, some fractures may occur spontaneously.

Classical deformity: The classical deformity resulting from a fall is that the leg is shortened and externally rotated, but 15% of fractures are impacted and there will be no deformity. Any elderly person who complains of hip pain or is unable to mobilise at their normal level of mobility, even without a history of a fall, should have an x-ray of the hip.

Learning bite

Have a very low threshold for x-rays of the hip if there is the slightest possibility of a fractured neck of femur.

Diagnosis of the type of fracture

It is important to diagnose the type of fracture as this influences treatment.

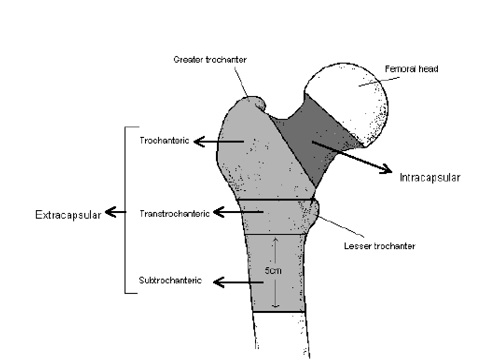

The usual classification of fractures is:

- Intra-capsular – from the subcapital region of the femoral head to basocervical region of the femoral neck, immediately proximal to the trochanters

- Extra-capsular – outside the capsule, subdivided into:

- Inter-trochanteric, which are between the greater trochanter and the lesser trochanter.

- Sub-tronchanteric, which are from the lesser trochanter to 5cm distal to this point.

Other terms used to describe these injuries are shown in Fig.1.

Fig 1: Anatomy of the proximal femur

Intracapsular fractures

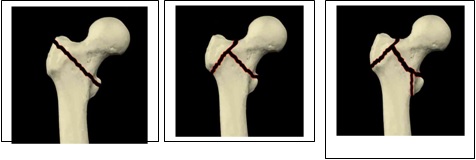

Types of intracapsular fractures include:

- Subcapital

- Transcervical

- Basal/Basicervical

What is the importance of an intracapsular fracture?

The importance of an intracapsular fracture is that a large proportion of the blood supply to the head of the femur comes via the capsule. In a retrograde direction from the medial circumflex branch of the femoral artery, which is considered to be disrupted in intracapsular fractures, especially those with displacement. As a consequence there is a risk of non-union and avascular necrosis.

For this reason, arthroplasty (either hemiarthroplasty or total hip replacement) may be indicated for these fractures.

Learning bite

There is a high risk of avascular necrosis and non-union in intracapsular fractures.

The Garden classification can be used to identify different types of subcapital, transcervical and basal fractures:

Type 1 – Impacted fracture or abduction fraction

Type 2 – Undisplaced

Type 3 – Some displacement

Type 4 – Grossly displaced

Examples of subcapital, transcervical and Basal/Basicervical fractures are shown below.

Extracapsular fractures include:

- Trochanteric

- Transtrochanteric/Intertrochanteric

- Subtrochanteric

There are many different classifications of trochanteric fracture but when describing the fracture to an orthopaedic surgeon, perhaps the most useful is to describe the number of parts that the femur has been divided into (see Figure 3).

- A two-part fracture is a single fracture line across the trochanteric region (Fig 1)

A three-part fracture is a comminuted fracture across the trochanteric region with the greater or lesser trochanter fractured (Fig 2)

A four-part fracture is similar to a three-part fracture, but with fractures of both the greater and lesser trochanters (Fig 3)

Learning Bite

There is a high risk of avascular necrosis and non-union in intracapsular fractures.

An elderly patient with pain in the hip following a fall must be assumed to have a fractured neck of femur until proved otherwise.

Other fractures that can occur with this mechanism are:

- Fractures of the pubic ramus

- Fractures of the acetabulum.

In addition to appropriate imaging, the BOA also recommends that the following investigations are done in the ED [1]

- Routine bloods (FBC, U&E, Group and save)

- ECG

- Pre-operative chest X-ray (except in younger fitter individuals)

Have a very low threshold for X-raying to exclude a fracture. Any elderly patient who falls should have an X-ray of the hip if they complain of pain anywhere between the waist or knee.

Any elderly person who complains of hip pain or goes off legs , even without a history of a fall, should also have an X-ray of the hip.

Learning Bite

Have a very low threshold for X-raying the hip if there is the slightest possibility of a fractured neck of femur.

X-rays

The usual X-rays obtained for a patient with a hip injury are:

- AP pelvis. This shows both hips for comparison and will also show other fractures (eg pubic rami) that may also occur in a fall.

- Lateral of the hip. This is essential as not all fractures will show on an AP X-ray

The neck of the femur will be at right angles to an AP X-ray when the hip is in about 100 of internal rotation. If the hip is externally rotated, the neck of the femur may appear foreshortened and this may make fractures less easy to see. If there is doubt on these X-rays as to the presence of a fracture, an AP X-ray centred on the hip may be of value.

Fractures are commonly missed. To avoid missing fractures look for:

- Shentons Line (see Figure 4): This is an imaginary line drawn up the inferior neck of the femur and extending along the inferior part of the superior pubic ramus. This should be smooth. If it is disrupted, this may indicate a fracture.

- Follow the trabeculae along the neck of the femur and ensure that they are intact.

- A sclerotic line across the neck of the femur may indicate an impacted fracture

- Look for steps in the cortex

Figure 4: Shentons line

If the X-ray is thought to be normal, there are two possibilities:

- Most likely is that the X-ray is normal.

- However fractures are not always easy to see and it is possible that there is a fracture that has been missed. If the clinical features suggest a fracture but the X-ray appears normal, it is important that the X-ray is re-examined and consider obtaining a second opinion

In the majority of cases, a normal X-ray means that there is no bony injury but about 1% of hip fractures are not visible on initial X-rays. There are no validated guidelines on the management of patients with hip pain following a fall but with no obvious fracture visible on an X-ray.

However a pragmatic approach to the problem would be:

- Give analgesia and try to mobilise the patient. If the patient walks well, there is no fracture and they can be discharged.

- If the patient cannot walk they will need admission

- Try again to mobilise the patient the following day: if they are still immobile, they will need further imaging to exclude an occult fracture.

The best form of imaging to exclude a fracture is an MRI (see Figure 5). If it is not possible to obtain an MRI, CT scan or a bone scan may be performed or further plain films obtained after 48 hours [1]

Figure 5: MRI showing Right trochanteric fracture in a patient with normal X-ray

Learning Bite

If there are clinical features of a fractured neck of femur but the X-rays are normal, further investigation is required to exclude a fracture.

Management of pain

Pain assessment in the elderly confused patient may be difficult but patients should be given analgesia. This should be done before a potentially procedure eg moving a patient in the X-ray department or moving a patient to a bed. The best method of giving systemic analgesia is to titrate doses of opiate intravenously. Entonox may also be useful. The most effective form of local analgesia is a local anaesthetic block (eg. fascio-iliaca or femoral nerve block). NSAIDs should be avoided because of the risk of gastrointestinal complications and their effect on renal function in the elderly [1]

The BOA [1] recommends that, in the ED, all patients should have:

- Diagnosis established

- Pressure relieving mattress

- Patient assessed for other injuries and medical problems

- Pain relief

- Routine bloods (FBC, U&E, Group and save)

- ECG

- Pre-operative chest X-ray (except in younger fitter individuals)

- Immediate fluid resuscitation with intravenous saline.

SIGN [2] recommend that early assessment, in the ED or on the ward, should include a formal recording of:

- Pressure sore risk

- Hydration and nutrition

- Fluid balance

- Pain

- Core body temperature using a low reading thermometer

- Continence

- Coexisting medical problems

- Mental state

- Previous mobility

- Previous functional ability

- Social circumstances and whether the patient has a carer.

They also advise use soft surfaces to protect the heel and sacrum from pressure damage and keeping the patient warm.

There is no evidence of benefit for traction [8]

Thromboprophylaxis

This is controversial and the balance of risks and benefits is complex in this group of patients. Mechanical methods are safe and are recommended. Undoubtedly heparin reduces the incidence of DVT and PE but routine use of heparin increases the risk of bleeding and wound complications and there is no proven effect on overall mortality [1]. NICE recommends that patients having surgery for hip fracture should be offered mechanical prophylaxis and pharmacological VTE prophylaxis.[4]

Mechanical VTE prophylaxis should be started at admission using (based on individual patient factors) one of:

- anti-embolism stockings (thigh or knee length)

- foot impulse devices

- intermittent pneumatic compression devices (thigh or knee length).

And this should be continued until the patient no longer has significantly reduced mobility.

In addition and provided there are no contraindications, NICE recommend the use of one of:

- LMWH, starting at admission, stopping 12 hours before surgery and restarting 612 hours after surgery

- UFH (for patients with renal failure), starting at admission, stopping 12 hours before surgery and restarting 612 hours after surgery.

- fondaparinux sodium, starting 6 hours after surgical closure. It should not be used pre-operatively because of the risk of an epidural haematoma if the patient had an epidural or spinal anaesthetic.

NICE recommend that this be continued for 28-35 days.

Rapid transfer to an orthopaedic ward is important. A clinical standard for both the BOA [1] and the College of Emergency Medicine (CEM) is that patients be transferred to a ward within 4 hours [9] to avoid pressure sores, confusion and pain. The CEM additionally recommends that X-rays should be performed within 60 minutes and that 90% of patients should be admitted within 2 hours.

Although it is important for patients to be transferred quickly to an orthopaedic ward, the majority of patients with this fracture have co-morbidity and they may have fluid balance problems because of diuretics, renal impairment etc.[10] They should have input from an orthogeriatrician[1], and consideration should be given to formal shared care.[10]

Orthopaedic management

Undisplaced intracapsular fractures (see Figure 6)

Figure 6: Undisplaced intracapsular fracture

While these can be treated conservatively, internal fixation (see Figure 7) allows early mobilisation and reduces the risk of the fracture displacing. Conservative treatment would probably only be recommended for patients who present late and who already show some healing or patients with a very short life expectancy (but even in these patients, surgery may make the patient more comfortable and easier to nurse).

Fig 7. Undisplaced intracapsular fracture treated with 3 lag screws

Arthroplasty is a much larger surgical procedure with more complications but may, rarely, be recommended in the very elderly.

Displaced intracapsular fracture (see Figure 8)

Figure 8: Displaced intracapsular fracture

There are a variety of treatment options.

- In internal fixation, the head of the femur is retained and surgical trauma is less, so there will be fewer acute surgical complications. However there is a significant risk of non-union and avascular necrosis and this leads to a significant (up to 36%)[1] need for re-operation.

- An arthroplasty is a larger and more traumatic procedure with a higher rate of acute complications (eg haematoma, infection, dislocation) but a much lower rate of requiring further surgery (6-18%). [1]

In general, younger patients will be recommended reduction and internal fixation but older patients (who are fit enough to stand the larger procedure), will be recommended an arthroplasty. This is usually a hemiarthroplasty (see Figure 9) as this is a smaller surgical procedure but a total hip replacement may give better results though this is unproven.

Figure 9: Fracture treated with a hemiarthroplasty

Extracapsular fractures (see Figure 10)

The British Orthopaedic Association states that the sliding or dynamic hip screw (SHS / DHS) (see Figure 11) is the standard against which other devices should be judged . [1] There are a number of different types of this device. Other methods of internal fixation are available but the superiority of the SHS has been proven in trials. These fractures can be treated with traction but this requires prolonged immobility with complications of that and this method of treatment is not usually done in the UK.

Figure 11: A sliding or dynamic hip screw

Patients on anticoagulants

Most elderly patients will have co-morbidities and many will be on anticoagulants.

The BOA recommends that, in patients on anticoagulants, surgery is postponed until the INR < 1.5. [1]. There is no evidence on whether there is any benefit to reversing anticoagulation using vitamin K or fresh frozen plasma [1]

There are risks of bleeding in operating on a patient on clopidogrel, and for elective surgery, it is often recommended that patients stop these types of anti-platelet drugs seven days before surgery but this is not practical for emergency surgery. It is necessary for surgeon, physician and anaesthetist to agree a compromise. [1]

Early surgery is associated with reduced complications but surgery should be performed during normal working hours. The BOA standard is that surgery should be performed within 48 hours [1]. The SIGN guidelines state that surgery should be done be done as soon as possible and within 24 hours if the patients medical condition allows.[2]

All patients will need rehabilitation.

Learning Bite

Patients should be fast-tracked through the ED [1], [10] and early surgery reduces complications.

While the prognosis following a hip fracture is very dependent on the degree of frailty before the injury and the pre-existing medical problems, there are some statistics that may act as a guide:

- The 30 day in hospital mortality varies in different series (8-13%) but is probably about 10% [1] though only about half is caused directly by the fracture.

- The incidence of DVT depends on how carefully it is looked for with incidences of up to 91% being demonstrated with routine venography[1]. It will also vary with thromboprophylactic measures taken.

- The incidence of pulmonary embolus (PE) on routine lung scans is 10-14% but the incidence of clinically apparent PE is only about 1% and the incidence of death due to PE is about 0.5% [1]

- Other complications include haematoma formation, superficial and deep infection, loosening of prostheses and peri-prosthetic fracture.

- The 12 month mortality is about 30% and this largely reflects co-morbidity.

- Most patients will have some long-term hip discomfort and about half will need additional walking aids. Only about half will return to their previous level of independence and 10-20% of patients admitted from home will need residential or nursing home care.

- Pressure sores are common but should be avoidable [11]

- Have a very low threshold for X-ray. You should X-ray:

- Any elderly patient who falls and has pain anywhere between the waist and the knee

- Any patient with hip pain or worsening of pre-existing hip pain , even in the absence of trauma

- Any elderly patient who is off legs for no obvious reason

- Be aware that a normal X-ray does not exclude a fracture.

- An isolated fracture of the greater trochanter is a minor injury that is treated by analgesia and mobilisation but a significant proportion of patients with this injury have an associated occult fracture of the trochanteric region and so further imaging (CT or MRI) should be considered. [12]

- British Orthopaedic Association. The care of patients with fragility fracture. Pub BOA, 2007.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Prevention and management of hip fracture in older people. Pub SIGN 2002

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Falls. The assessment and prevention of falls in older people. Pub NICE 2004. View pdf

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Venous thromboembolism: reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) in inpatients undergoing surgery). Pub NICE 2007.

- Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ, Robertson MC et al. Interventions for preventing falls in elderly people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1997 issue 4. Art No.: CD000340. DOI 10.1002/14651858.CD000340.

- Gates S, Fisher JD, Cooke MW, et al. Multifactorial assessment and targeted intervention for preventing falls and injuries among older people in community and emergency care settings; systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2008;336:130-3.

- Clinical Effectiveness Committee, British Association for Emergency Medicine. Standards for Accident and Emergency Departments 2004. pub BAEM

- Callum KG, Gray AJG, Hoile RW et al. Extremes of Age. 1999 pub. National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths. (NCEPOD)

- Craig JG, Moed BR, Eyler WR, van Holsbeeck. Fractures of the greater trochanter: intertrochanteric extension shown by MR imaging. Skeletal Radiology 2000;29:572-6.

- Further guidance has been published by NHS Evidence. Ref: NHS Evidence. Annual Evidence update on Hip Fracture 2009.

13 Comments

Excellent refresher on types of hip fractures.

excellent

useful revision

helpful

Very succinct and useful guide to management of hip fractures. Some useful tips to avoid missing fractures in the elderly.

Nice concise information

good comprehensive update on hip fractures

Excellent review.

Good and concise

Very comprehensive. A usefull guide to managing hip pain/injury

Very informative

good

it gives a clear guide to suscepted NOF in ED. Very helpful!!