Authors: Charlotte Elliott, Aaron Borbora / Editors: Mark Buchanan, Paul Johnson, Lauren Fraser / Codes: MaC2, MaP2, SLO4, TC6, TP10 / Published: 21/11/2019

Thousands of patients present to the emergency department each year with injuries. It is not unusual, especially on a Friday or Saturday night, to see multiple types of injuries during a shift – the elderly lady who has fallen out of bed and hit her head, the teenager who has deliberately cut her wrist with a razor blade, the patient who alleges assault with a baseball bat the list goes on.

Correct descriptions of injuries are vital to ensure good record keeping, a core component of the GMC’s Good Medical Practice. Correct descriptions of injuries are also vital in cases of alleged assault where the notes form the basis of potential legal proceedings. When you are thrust your clinical notes several months after seeing the patient and asked to write a police report, it is likely you have forgotten the patient’s injuries and so have to rely on your notes. Incorrect descriptions may lead to professional embarrassment and potentially injustice for the victim.

You wouldn’t describe a wheeze as a crepitation so don’t describe an abrasion as a laceration.

While the terms wound and injury maybe used interchangeably, this can be incorrect, as a wound involves a break in the skin.

Documentation of an injury should meet the criteria as described in Churchills’ Medicolegal Pocketbook:

- Documentation of where and when examination took place.

- Accurate documentation of the type of injury (laceration, abrasion, incision, etc) – does this match the alleged mechanism of injury?

- Documentation of the shape of the injury, its location and measurement from a fixed anatomical point. Diagrams can be employed here.

- Documentation of colour.

- Documentation of the presence or absence of active bleeding or clot.

- Whether it appears to be showing signs of healing.

- Documentation of what treatment, if any, was given.

Let’s look at some injuries.

Abrasions

Abrasions (grazes or scrapes) are typically the result of tangential blunt force trauma exerting a dragging or frictional force to the superficial skin. Abrasions do not usually penetrate the full thickness of the epidermis, but may do so focally. Abrasions may bleed due to interruption of the dermal papillae. Typically, the end opposite to the point of impact shows heaped up epidermis (and therefore may have some forensic significance in determining the direction of the apparent force). Abrasions can be of varying type such as directional (brush type) resulting from contact with a rough surface (e.g. “road rash”) or finger nail scratches which are often short and curved. Assessment of age of abrasions in isolation may be difficult, but the absence of bleeding, the presence of scabbing, along with the appearance of any associated bruising may be helpful.

Figure 1. Abrasion to the forehead falling a fall.

Figure 2. Abrasion to the left cheek following contact with the floor.

Bruises

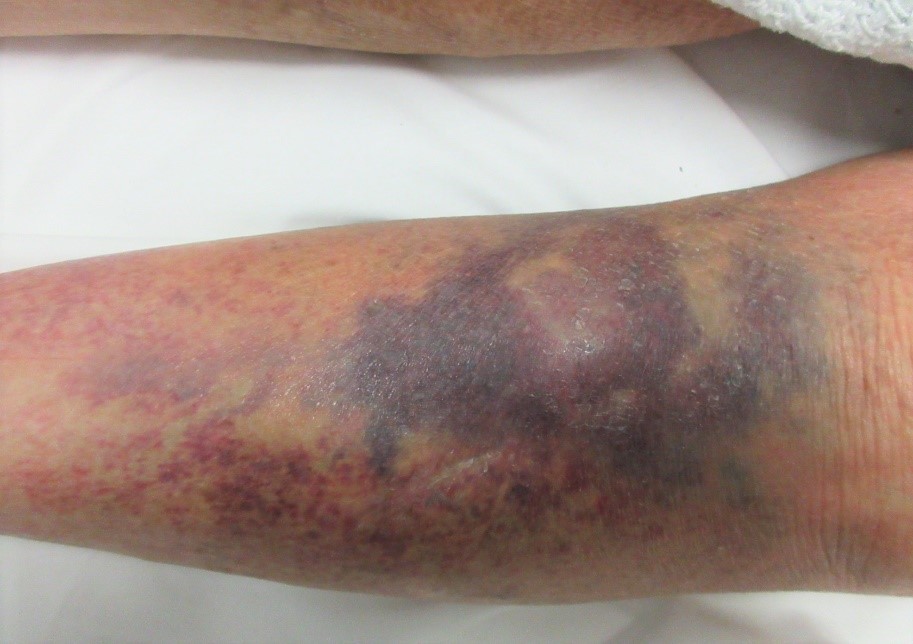

Bruises are extravascular collections of blood caused by various types of blunt force [Fig 3]. They may be patterned and can reproduce the shape of the weapon or object responsible (e.g a shoe or fingertip bruises where a grip has been applied. Sometimes a characteristic tramline bruise results from forceful contact with a rounded or squared-off weapon such as a baseball bat [Fig 5].

However, the bleeding can track under the skin which leads to pattern disruption. Bruises are often larger where the skin is lax or there is underlying bone (in contrast to the palms or sole of the feet where the skin is thick bruises are seldom seen). In these areas, the bruise may enlarge and track over time. It is important to appreciate this phenomenon if your examination takes place sometime after the injury occurred. For example, a large bruise to the anterior scalp or forehead can track into the periorbital soft tissues, which could be misinterpreted as the site of the initial impact.

Assessment of the age of the bruise is not always reliable. Colour changes do not occur in a predicable or linear fashion. The most helpful colour is yellow, which does not appear in bruises less than about 18 hours old.

Figure 3. Focal early yellow change in a bruise. Note the difficulty in assessing the size without the inclusion of a scale.

Figure 4. Finger-tip type bruising.

Figure 5. Typical tram-line type bruising.

Haematomas

Haematomas are palpable collections of blood, usually in muscle and soft tissue. A common example is the periorbital haematoma or “black eye”. This is often caused by a direct blow, in which case there may be an associated abrasion or laceration. Other causes include the tracking of blood from bruise to the forehead or an orbital plate fracture from contre-coup damage after fall-related impact to the back of the scalp. The scalp should be checked carefully for such injuries and imaging requested as required.

Figure 6. Periorbital haematoma. Note the abrasion above the eyebrow.

Bites

Bites are a pattern of injury produced by human or animal dentitions and associated structures. Bite marks are classified as a form of crush injury because the tooth compresses the skin which leaves an indentation or break. The injury usually consists of abraded and bruised components and often have a curved profile. Bites can be a useful source of DNA and can be expertly analysed by forensic odontologists. Because of the potential for DNA evidence, before cleaning such an injury wet and dry swabs (to capture saliva and DNA) should be considered if clinically feasible and after discussion with the Police.

Figure 7: A human bite to the arm. Note the curved appearance.

Lacerations

Lacerations are full thickness tears to the skin caused by blunt force trauma where the tissues are crushed or torn apart by the object or weapon.

Lacerations typically exhibit the following features:

- Often gaping

- May be irregular, but can also be linear

- Associated bruising (from being crushed)

- Associated abrasions to the edges

- Tissue bridges in depth of the wound (in contrast the incised wounds)

- Rarely self-inflicted

- Presence of intact hairs which cross the wound (in contrast to incised wounds)

- Relatively little blood loss (unless on the scalp or intra-orally)

- Can be associated with fractures (e.g underlying depressed skull fracture)

Figure 8. A scalp laceration.

Figure 9. Laceration to the chin.

Figure 10. Lacerations to the back of the head – note how the edges are irregular and the wound is gaping.

Incised wounds

Incised wounds follow sharp force trauma and maybe divided into stab (or puncture) wounds and cuts (or slash) wounds. A stab wound is deeper than it is long but a cut is longer than it is deep. The shape of the wound can sometimes give an indication of the type of object used to inflict it, eg a knife or sharp edge of a broken glass, but this may be difficult to determine in slash wounds. An incised wound can be caused by anything sharp which impacts the body with sufficient force to penetrate the skin. Wounds from heavy blades such as axes and machetes can have components of both lacerations and incised wounds.

Incised wounds typically exhibit the following characteristics:

- The skin wound is often linear, but can be jagged and irregular for example if caused by broken glass or bottles or if the knife has moved in the wound

- The wound edges are cleanly divided

- There is often no adjacent bruising of the skin edges

- Hair follicles are cleanly cut

- The wound bleeds when the injury is sustained. Bleeding can be heavy if vessels are involved.

Figure 11: Slash wounds to the leg.

Figure 12: A stab wound.

Petechiae

Although not strictly an injury, the documentation of the presence or absence of pin-point petechial haemorrhages (or petechiae) can prove to be of central forensic importance.

Petechiae may develop after alleged airway obstruction or from the application of forceful neck pressure (strangulation). These need to be documented and photographed at the earliest opportunity as they will disappear quickly. If a patient is seen in circumstances where an asphyxial component of an assault is reported, it is important to examine the face, especially around the eyes and eyelids, after makeup has been removed.

Petechiae can best be seen inside the eye lids, and in the mouth. It is important to specifically look for petechiae or else these may easily be missed. Other injuries relevant to the alleged assault, such as finger nail abrasions and fingertip bruising around the external airway and on the neck must also be carefully looked for.

Figure 13. Petechial haemorrhages.

Always obtain and record a verbatim account of how the patient alleges the injury was sustained.

It is recommended that a ruler, scale, or tape measure is used to accurately measure the size of injuries and also measure the distance from a fixed structure.

Ideally, photographs should be taken before any treatment is commenced. These can be taken by the Police on their Body Cameras (if worn), by Medical Photography, or on a Departmental Camera.

Body maps can be used to document where the injuries are.

Wound closure methods will vary from clinician to clinician and patient to patient. In general though, if there is an open wound such as a laceration or an incision this will need to be cleaned and closed either with steristrips, glue or sutures. In an audit carried out by the authors which reviewed the notes of patients who had presented to the ED with an alleged assault they were surprised to see that a described abrasion had been sutured! Closure of the wound may allow you to think about your documentation too if the wound is being closed it is likely to be an incision or laceration. If the wound isn’t being closed it is likely to be an abrasion or a bruise.

Always consider a tetanus status especially with deep contaminated wounds.

Remember that there maybe foreign bodies in the wounds and the wound may need to be explored and washed out. This is best done under local anaesthetic. If you are unsure then it is always best to ask someone.

The injury may need to be x-rayed to look for foreign bodies or fractures.

Bites should be managed according to local protocol which usually involves thorough cleaning of the wound (sometimes with debridement), treatment with antibiotics, consideration of tetanus cover and Blood Bourne Virus prophylaxis. Don’t forget to consider swabbing the bite for DNA evidence.

Never pass drains or other lines through stab wounds. This can distort the appearance of the injury. Similarly, do not incorporate injuries into surgical incisions – for example a thoracotomy.

Clinical notes are extremely useful if recorded correctly in cases of alleged assault. Better note keeping will ensure medical records and police reports are of high standard, helpful to the courts and useful to doctors required to give evidence relying on their notes as a reminder of the case.

For an injury description to be helpful it must be accurate. Poor documentation may result in professional embarrassment if notes or evidence is relied on in court.

Doctors are often bad at estimating sizes of wounds if you do guess then make sure you record that your measurement is only approximate. The best and recommended way to record the size of the wounds though is to measure it properly with a tape measure and photograph it with a scale.

Never pass drains through injuries or incorporate them into surgical incisions.

- Bourne C, Jenkins M, and Brewer K. (2014). Estimation of laceration length by emergency department personnel. West J Emerg Med, 5(7), pp. 889-91.

- Forensic Medicine. (2015) Wound Documentation. [Accessed 1 Jul. 2019].

- General Medical Council. (2013). Good Medical Practice. [Accessed 1 Jul. 2019].

- Machin, V. (2003). Churchill’s Medicolegal Pocketbook. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- Peterson N, Stevenson H, and Sahni, V. (2014). Size matters: how accurate is clinical estimation of traumatic wound size? Injury, 45(1), pp. 232-6.

- Wyatt J, Squires T, Norfolk G, and Payne-James J. (2011). Oxford Handbook of Forensic Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press.

7 Comments

good overall and brief reminder of wound management

Informative update on wounds & management

Good article for every one but especially ANPs

good read

good revision of wound care and emphasis on documentation

excellent

Excellent module on Soft Tissue and Skin Injury Descriptions in ED.