Authors: Janet Skinner, Andrew Paul Stevenson / Editor: Janet Skinner, Phil Delbridge / Reviewer: Louise Burrows / Codes: ACCS LO 2, GP1, PC1, SLO1, SLO5, SuP1 / Published: 07/03/2022

This article covers the generic assessment and management of abdominal pain without shock.

Patients with acute abdominal pain are a common reason for attendance at the emergency department (ED) and account for approximately 10% of all attendances [1].

Patients can be difficult to assess and make an accurate diagnosis in the ED.

It is important that we have strategies to identify those patients who require admission, and recognise those patients that need resuscitation.

This session covers the generic assessment and management of the patient with abdominal pain without shock. The specific management of abdominal conditions for example appendicitis, will be covered in additional sessions.

Learning Bite

Abdominal pain is the most common surgical emergency to present to the ED.

Aetiology of Abdominal Pain

Acute abdominal pain is normally thought of as pain of less than one weeks duration. To aid initial diagnosis, investigation and management, causes of abdominal pain can be categorised into one of the five areas displayed (Fig 1) [1,4].

Fig 1. Aetiology of abdominal pain

- Oesophagitis

- Gastritis

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Gallstone disease

- Pancreatitis, bowel obstruction, appendicitis

- Diverticular disease

- Inflammatory bowel disease, ischaemic bowel, gastro-enteritis

- Acute liver failure

- Incarcerated hernia

- Constipation

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Ruptured ovarian cyst

- Renal colic

- Pyelonephritis

- Urinary tract infection

- Testicular torsion

- Epididymo-orchitis

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Myocardial infarction

- Pneumonia

- Diabetic ketoacidosis

- Hypercalcaemia

- Mesenteric adenitis

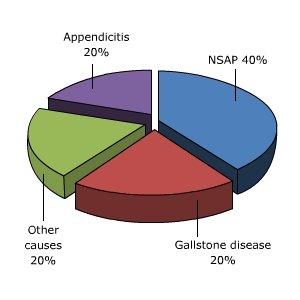

There are many causes of acute abdominal pain, although in terms of ED presenters the following approximate ratios are applicable (Fig 2) [2,3].

- 40% will have a final diagnosis of non-specific abdominal pain

- 20% appendicitis

- 20% gallstone disease

- 20% other causes

Learning Bite

Almost half of all patients who present to the ED will ultimately be classified as having non-specific pain.

Pathophysiology of Pain

Pain associated with the abdomen falls in to one of three types and it is important to identify this at the earliest possible stage.

Visceral Pain

The autonomic nervous system innervates the abdominal organs and produces vague, poorly localised pain in response to organ stretch (Fig 3).

Fig 3. Autonomic nervous system and visceral pain

If these organs are affected by peristalsis then this pain can appear intermittent or colicky in nature. Organs are innervated bilaterally so pain is often felt in the midline even if the organ is not actually positioned in the midline. Visceral pain is normally localised by the patient to the embryonic site of the organ, which may be different from the actual site, for example, the periumbilical pain of early appendicitis (Fig 4).

Fig 4. Embryonic development of the gut

Parietal (somatic) pain

This type of pain is due to irritation of the parietal peritoneum and is well localised to the site of the organ, for example the right iliac fossa (RIF) pain of later appendicitis [4].

Referred pain

Pain may be felt at a distant or referred site to the organ due to misinterpretation of stimuli by the brain, again based upon embryonic development of the nervous system. An example of this would be diaphragmatic irritation due to blood can be felt at the shoulder tip [1].

Pointers toward referred pain include an apparent lack of expected abnormalities on examination. For example, a normal shoulder examination, in a patient with shoulder pain.

It is vital to take an accurate pain history as this can provide important information.

There are four key questions to ask about abdominal pain:

- Onset sudden or gradual

- Duration or recurrence of the pain

- Character or nature of the pain

- Location of the pain

Onset Sudden or Gradual

Sudden onset abdominal pain is suggestive of the following:

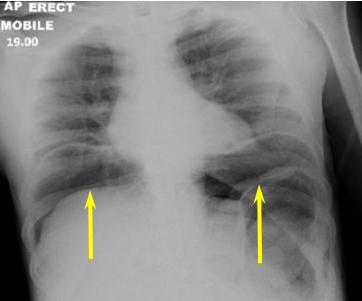

- Perforation of a viscus (Fig 1)

- Peptic ulcer

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Rupture of an aneurysm

- Impaction of a stone as in renal colic

Fig 1. Erect Chest x-ray

Duration or Recurrence of the Pain

Recurrent symptoms may indicate the following:

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Renal colic

- Gallstone colic and diverticulitis

In females, the following may be related to the menstrual cycle:

- Mittelschmerz

- Endometriosis

Character or Nature of the Pain

- Sharp, constant pain worsened by movement may represent peritonitis.

- Pain more marked than physical findings suggests ischaemic bowel or pancreatitis.

- Pain due to inflammation of an organ tends to come on gradually and results in guarding on examination.

- Pain due to obstruction tends to be intermittent and come in waves (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Abdominal X ray showing small bowel obstruction (arrowed)

Location of the Pain

Pain radiating to the back may represent aortic aneurysm rupture, peptic ulcer disease or pancreatic pathology (Fig 3).

Fig 3. CT showing aortic aneurysm (arrowed)

Furthermore, associated symptoms will provide further information on the patients condition (Table 1)

Table 1. Associated symptoms for abdominal pain

Visual Examination

The first examination made will be the one performed when you first meet the patient. Important information can be gathered by looking at patients from the end of the trolley.

Question

What should you look for?

Answer

You should determine whether they look ill or in pain. Patients who appear comfortable and apparently well, often are, whereas those who are anxious, in obvious pain, pale or clammy often are not.

This may appear obvious but is often forgotten when presented with a confusing array of information. It may also guide the choice of immediate therapy and investigation.

Abdominal Examination

Fig 4. The four abdominal quadrants and nine regions.

Traditionally, for the purposes of examination the abdomen has been split into four quadrants or nine regions. A simplified classification is shown (See Fig 5) [1,2,4].

It is important to gently palpate each of these areas looking at the patients face for signs of pain before proceeding to deep palpation.

On examination, note any tenderness or guarding, for example, tender to light palpation in the suprapubic area but without signs of guarding.

It is important to reassess the abdomen regularly as serial examinations by the same physician may reveal worsening pathology e.g. peritonitis.

Do not forget to check for organomegaly as this is an important part of the abdominal examination.

Fig 5. Simplified abdominal examination regions

Learning Bite

Careful and serial clinical assessment of the abdomen is a key aspect of a patients ED management.

Risk Assessment Tools

There are very few specific risk assessment tools for patients with abdominal pain. One of the few conditions to have a widely used risk assessment tool is pancreatitis.

Question: Can you think of any higher risk groups that may present with abdominal pain to the ED?

Answer:

- Patients with co-morbidities (e.g. diabetes)

- Elderly patients

It is necessary to maintain a low threshold for admission in patients from these at risk groups.

Elderly patients have an increased mortality due to co-morbidities, increased incidence of serious and rapidly progressive pathology and atypical signs [1]. They are also much less likely to have non-specific abdominal pain.

When assessing patients with acute abdominal pain, it is important to be aware that not all patients follow all the rules. Certain diagnoses can be notoriously variable in their clinical presentation. For example, pain from a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm can be felt in a variety of locations including the back, flanks and legs. Pregnancy distorts the normal anatomy and can cause pain from appendicitis or other acute pathologies to be experienced in atypical sites. It is important therefore to keep an open mind when formulating your differential diagnoses.

Learning Bite

Any elderly patient with abdominal pain is much more at risk of a poor outcome.

The management of a patient presenting with abdominal pain might include the following:

- It may be necessary to resuscitate if signs of sepsis or haemodynamic instability are shown, furthermore if there are any concerns or patient is unwell, discuss with ED senior.

- Morphine IV titrated to effect. A Cochrane review states that there is no evidence that opiates mask the signs of peritonism or lead to a delay in diagnosis. Analgesia should never be withheld until the patient has seen the surgeon[7].

- There is no evidence for anti-spasmodics like Buscopan in the management of acute pain [8].

- IV anti-emetics Metoclopramide theoretically increases gastric emptying so other anti-emetics such as cyclizine and ondansetron have been favoured although there is little evidence to support this [9].

- Anti-pyretic (IV paracetamol if necessary).

- It may be necessary to use a Nasogastric tube if a bowel obstruction is present.

- It may be necessary to use a Urinary catheter if the patient is unwell or peritonitis is suspected.

- Broad spectrum IV antibiotics if there are signs of sepsis or peritonitis.

- Keep nil by mouth if acute surgical pathology suspected and give IV crystalloid fluids where required (eg. dehydrated, shocked).

- Refer to surgical team, if indicated.

Admit/Discharge Decision Making

If there is no evidence of a significant surgical pathology, the patient is pain free and has a normal examination then it is reasonable to discharge the patient home with clear advice on when to return. Patients with acute abdominal pain will normally be given appropriate safety netting advice before being discharged, for example to return if significant pain recurs or they become otherwise unwell.

It may also be appropriate to arrange a review 12-24 hours later, for example as a day attender to the Surgical Assessment Unit. Patients with suspected biliary colic who have pain that settles can often undergo USS followed by discharge or be brought back the next day for an USS.

Elderly patients and those with significant co-morbidity should be admitted in most cases as they are at much higher risk of serious pathology. An RCEM standard is that all patients over the age of 70 presenting with abdominal pain should have consultant sign off.

It is not uncommon to reassess a patient who initially presented with severe pain (eg. requiring morphine) to find them pain free with a soft abdomen. In these situations, remember that pain may recur. In general, any patient who has experienced pain requiring strong opiates is likely to need admission for observation and possible further investigations.

Learning Bite

Patients with abdominal pain discharged from the ED should have clear safety netting advice including when to return.

Surgical Management Treatment Options

The surgical management of patients with acute abdominal pain will depend on the specific pathology, but this is not always known. In general, there are two broad strategies.

- Conservative management (wait and see)

- Surgical intervention

Wait and see:

Allowing time to pass can be a helpful diagnostic aid. Nearly half of patients with acute abdominal pain receive no specific diagnosis but can be safely discharged if investigations are normal and symptoms settle. Many of these patients will be discharged directly from the ED with a wait and see strategy at home. Others will be admitted for closer monitoring and may be discharged by the surgical team at a later point, or the passage of time and the results of further investigations may allow for a definitive diagnosis to be made. The role of serial clinical examinations, best performed by the same senior surgeon, is central when it comes to monitoring these patients.

Imaging:

Imaging options include ultrasound, CT and endoscopy. Decision making will be guided by the clinical presentation and suspected diagnosis.

Most patients with suspected acute surgical pathology will undergo imaging prior to surgical intervention (usually in the form of CT scanning) to help elucidate the nature of the pathology and guide the approach to surgery.

In other patients, where there is more diagnostic uncertainty, imaging may play a role in confirming or refuting certain suspected diagnoses. However, it is important to bear in mind that although CT is ‘non-invasive’, it is not without risk. As an example, it is estimated that a multiphase abdomen-pelvis CT scan performed in a 20-year-old female carries a 1/250 lifetime attributable risk of developing cancer as a direct result of the radiation exposure.[12] In younger patients in particular there should be a higher threshold to perform imaging that exposes to radiation.

Fig 1. CT Image of AAA (arrowed)

Surgical options:

- If a surgical condition is found then the patient may undergo a specific abdominal procedure, such as appendicectomy.

- If a surgical cause is likely, but the nature remains unknown, then surgeons may undertake a diagnostic laparoscopy.

- A diagnostic laparoscopy will give a cause for a patient’s abdominal pain in around 80% of cases.[13]

- Surgeons will make the decision to operate by weighing up the risks and benefits of laparoscopy versus conservative treatment.

- In critically unwell patients, or those too unstable to undergo laparoscopy, it may be appropriate to perform an exploratory laparotomy.

The following conditions indicate the need for operative intervention:

- Presence of peritonism

- Frank peritonitis

- Evidence of perforation

- Failure to settle with non-operative measures [10]

Learning Bite

Reassessment of abdominal signs is a key aspect to surgical decision making in a patient with abdominal pain.

Non-surgical Causes of Abdominal Pain

It is important to remember that both medical and gynaecological problems may present with abdominal pain. The following are non-surgical causes of abdominal pain:

- Acute myocardial infarction (MI)

- Diabetic keto-acidosis (DKA)

- Hypercalcaemia

- Pneumonia

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Urinary tract infection (UTI)

Acute myocardial infarction (MI)

Consider based on history. If in any doubt obtain an ECG. MI (especially inferior MI) can present with minimal or even no chest pain.

Diabetic keto-acidosis (DKA)

A history of diabetes with possibly some prodromal infective symptoms and vomiting may be clues but a bedside glucose should always be taken and followed up with serum/urinary ketones and arterial blood gas. To complicate matters further it is important to remember that some abdominal pathology may be the initiating factor in DKA.

Hypercalcaemia

- This can present with abdominal pain, either non-specific generalised pain or related to renal colic.

- Other features may be present including vomiting, weight loss, change in bowel habit and anorexia.

- Check serum calcium and albumin level (remember to correct calcium for hypoalbuminaemia).

Pneumonia

This may present as non-specific upper abdominal pain. Vomiting may be a feature and respiratory symptoms may be minimal. Be alert to unexpected hypoxia and obtain a CXR.

Inflammatory bowel disease

- This straddles the distinction between surgical and medical condition.

- It may present with abdominal pain during acute flare but can also present due to perforation or obstruction.

- A previous or prodromal history may be present but may be short in a new diagnosis.

Urinary tract infection (UTI)

- Usually presents with lower abdominal pain but may radiate into the flanks or be primarily located in one renal angle in pyelonephritis.

- Departmental dipstick analysis may give a clue but if suspicious send for urgent gram stain.

Learning Bite

Maintain a high index of suspicion for medical conditions that can cause abdominal pain.

Functional and Chronic Abdominal Pain

Any patient who represents to the ED with the same symptoms within a few days of discharge is at high risk of significant pathology.

- A few patients will present to the ED with recurrent or chronic abdominal pain. It is important to treat each presentation at face value.

- There is a higher mortality in frequently attending patients and if in any doubt seek senior staff guidance.

- Consider functional abdominal pain in patients who have had previous repeatedly normal investigations and multiple presentations.

- Consider social and medical input into these patients through case management.

- It may be appropriate to consider referral to chronic pain or mental health teams.

Learning Bite

Never dismiss a patient who has repeated presentations with abdominal pain. Seek senior input where necessary.

Assessment Pitfalls

Pitfalls in assessing ED patients with abdominal pain include the following:

- Do not forget to examine the hernial orifices so as not to miss an incarcerated hernia.

- Do not rely too heavily on inflammatory markers – these are non-specific.

- Failure to perform an hCG in all females of child-bearing age may mean missing an ectopic pregnancy.

- Beware discharging the patient who has experienced severe pain (eg. requiring strong opiates) as this pain may return and these patients often need a period of observation.

- Do not forget that medical conditions can present with abdominal pain. It is important not to miss an inferior MI or DKA.

- Ruptured AAA can present with a variety of different patterns of pain. Have a high degree of suspicion especially in patients with risk factors (eg. male, age >50, smoker, hypertensive, positive family history).

- Be aware that pregnancy distorts normal anatomy and clinical presentation may be atypical.

- The elderly patient with abdominal pain is more likely to have serious pathology and can be harder to diagnose.

Key Learning Points

- 40% of patients presenting to the ED will ultimately have a diagnosis of non-specific abdominal pain.

- Analgesia should never be withheld until the patient has been assessed by a surgeon.

- CT and USS are the imaging modalities of choice in a patient presenting with abdominal pain.

- Plain x-rays are of little benefit.

- Raised WCC and CRP are helpful but non-specific and will be raised in a multitude of causes of abdominal pain. Inflammatory markers can also be normal in the presence of significant pathology, especially early in the disease course.

- The elderly with abdominal pain are much more at risk of having a significant pathological cause for their abdominal pain.

- Taking an accurate pain history and performing a thorough abdominal examination is the key to the ED assessment of patients with abdominal pain.

Learning Objectives

Having read this article you will now be able to:

- Demonstrate physiological principles to your clinical assessment of the abdomen and to formulating a differential diagnosis.

- Recognise the importance of history and examination in determining the cause of abdominal pain.

- Demonstrate a rational approach to diagnostic investigations in patients with abdominal pain.

- Identify non-surgical causes of abdominal pain and manage them appropriately.

- Fairclough PD. Gastrointestinal disease. In: Kumar P, Clark ML, eds. Clinical Medicine. 5th edn. New York: Elsevier, 2005.

- Patterson-Brown S. The acute abdomen. In: Garden OJ, Bradbury AW, Forsythe JRL. 5th edn. Principles and Practice of Surgery. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2007:332-340.

- King KE. Abdominal Pain. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. Alibani: Mosby, 2006:1343-1354.

- Gallacher J. Gastro-intestinal Emergencies, Acute abdominal pain. In Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS et al., eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. McGraw-Hill, 2003:487-593.

- Palmer LR, Patterson-Brown S. Alimentary tract and pancreatic disease. In Haslett C, ed. Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2006:599-683.

- Haldane C. Does a normal CRP exclude serious pathology in the patient with acute abdominal pain. BestBets 2008.

- Laméris W, van Randen A, et al., Imaging strategies for detection of urgent conditions in patients with acute abdominal pain: diagnostic accuracy study. BMJ. 2009 Jun 26;338:b2431.

- Manterola C, Astudillo P, Losada H, et al. Analgesia in patients with acute abdominal pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jul 18;(3):CD005660.

- Macway-Jones, K. Buscopan in abdominal colic. BestBets 2003.

- Hassan, Z. Is cyclizine better than metoclopramide in patients with moderate to severe abdominal pain? BestBets 2005.

- O’Kelly T, Kruywoski Z. The acute abdomen and laparotomy. In: Monson JRT, Duthie G, O’Malley K, eds. Surgical Emergencies. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1999: 85.

- Smith-Bindman R, Lipson J, Marcus R, et al. Radiation Dose Associated with Common Computed Tomography Examinations and the Associated Lifetime Attributable Risk of Cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(22):2078-86.

- Decadt B, Sussman L, Lewis MP, et al. Randomized clinical trial of early laparoscopy in the management of acute non-specific abdominal pain. Br J Surg 1999; 86(11):1383-6.

45 Comments

Very good and well structured article.

Regarding chronic abdominal pain presenting to ED, certain rare conditions could be picked up by emergency physicians for example Porphyria or Familiar Fever (e.g Mediterranean).

Nice recap of abdominal pains and its assessment and management

useful and practical

Interesting overview

very useful

Good, structured review of approach to abdo pain

short but comprehensive coverage of pathophysiology, DDs, management. an area that would need further consideration would be on abdominal POCUS for AE clinicans to identify appendicitis, gall stones and gyn conditions.

Comprehensive &insightful

Most missed diagnosis in ED are from Abdomen

very elaborate, yet concise. This will sure be helpful in my practice

Very well explained,will help me in my clinical practice

Simple and well structured. Great for ED patients

comprehensive review of causes of abdominal pain .

A very comprehensive and detailed review of a common presentation to the emergency department.

Great piece, with many important learning points.

Informative and concise. Very helpful

Very well detailed review of the basics of abdominal pain clinical assessment.

nice update

very informative, covered all major points

very useful

Excellent and concise

Nice wrap up of the approach to abdominal pain

Good module thanks

useful module, easy to follow.

Very useful!

Excellent and concise module for recapping acute abdomen.

Well produced and relevant content. Many thanks

very useful module in ED mgt. of abdominal pain cases

Very informative & to be aware of the pitfalls

….very useful module in ED

NICE AND SIMPLE

Greatly module. Systematic examination and the other none intestestinal causes.

Informative and well structured

A very well narrated ‘back to basics’ module on the assessment of acute abdo pain in ED.

A succinct and practical approach to evaluation of abdominal pain. Excellent piece as it is all encompassing!

Very goo article. Thank you.

very useful module

good revision

Very structured approach to common ED presentation

Thanks

good revision

good review of the approach to abdominal pain

good module, enjoyable learning, hits the areas of concern in learning

Thank you.This was concise and touched on significant learning points for me as an ED clinician,

Good reminders including to consider medical causes of patients presenting with abdo pain

Extremely simple and pragmatic approach to the complex topic of abdominal pain. Thank you